Around 7 pm EST last Friday evening (February 24), the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) issued long-awaited proposed regulations regarding the continued use of telehealth to prescribe controlled substances in cases where patients have never been treated in-person by the prescriber before. (I want to thank my colleague Erin Grossmann for helping to dig our way through the regs once they were released!)

As you may recall, the DEA had issued broad waivers during the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE) to allow for the use of telehealth to prescribe controlled substances even for initial encounters. Many stakeholders—telehealth advocates, physicians, and patients—had been waiting with bated breath to see what the DEA would do once the COVID-19 PHE ends on May 11. Would the DEA make the telehealth waivers permanent, or would the DEA choose to pursue a more tailored approach? What flexibilities would the DEA specifically provide to buprenorphine prescriptions?

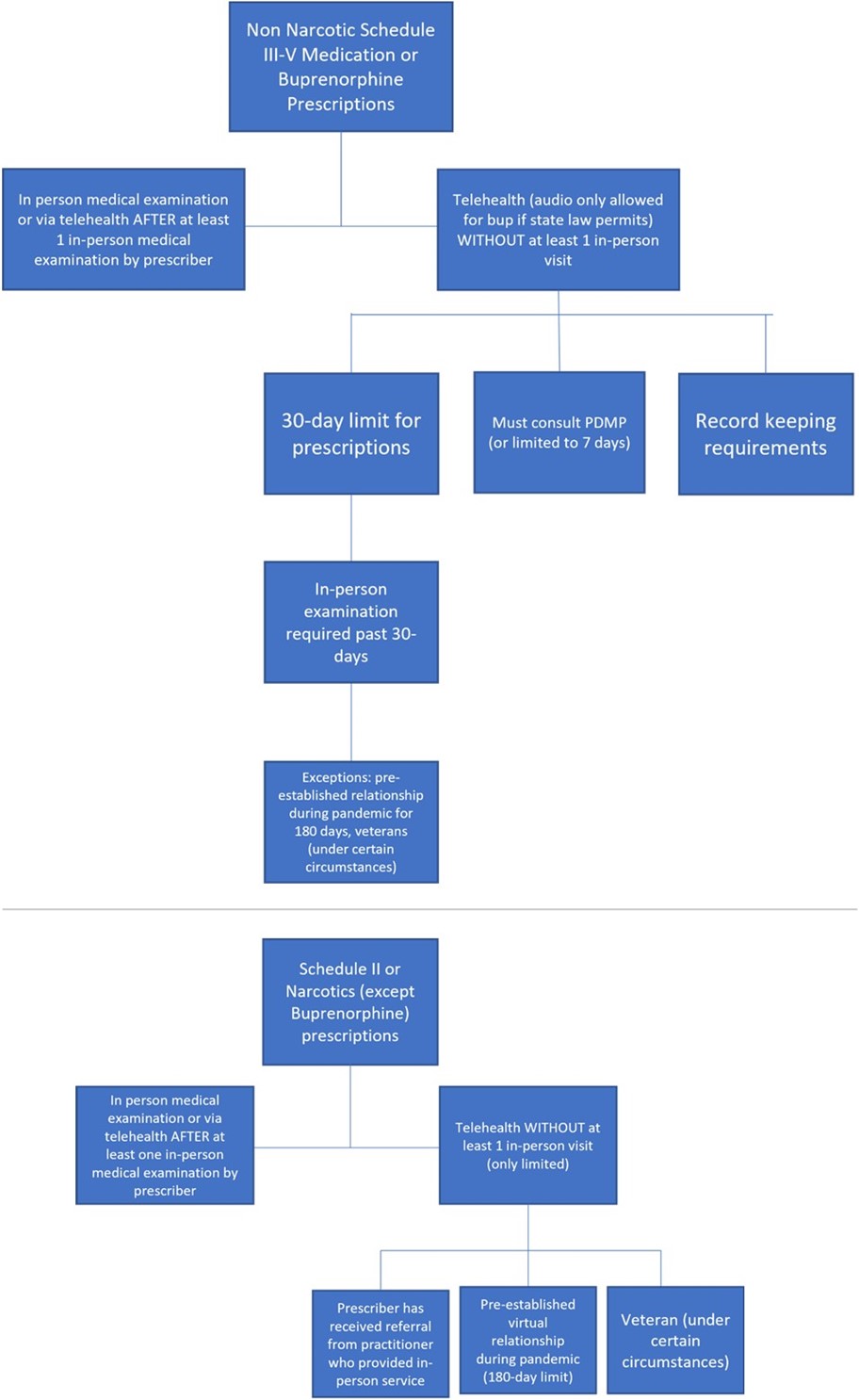

Well, much to the dismay of staunch telehealth advocates, the DEA chose to take a narrower path forward. I’ll start with a really positive development! In one of the two regs the DEA issued, the DEA is proposing to continue to allow the use of telehealth to initially prescribe buprenorphine (but not methadone) for the treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD). In other words, even if you as an emergency physician (or any other DEA-licensed physician or practitioner) have never seen the patient before, you are allowed to prescribe buprenorphine via telehealth for the treatment of OUD. If allowed by state law, a physician or other practitioner would not only be allowed to prescribe buprenorphine after an audio-video telehealth encounter but could also prescribe the medication after an audio only (by phone) visit—which does increase access to care, especially in rural and underserved communities.

However, in these circumstances, the DEA is proposing a prescription limit of 30 days (it can be multiple prescriptions as long as the total number of days does not exceed 30), after which an in-person examination is required in order to receive refills. The in-person examination can be conducted by the prescriber or by another DEA-registered practitioner. If the in-person examination is done by another practitioner, the prescriber has to participate remotely in a real-time conversation with the practitioner who conducts the in-person examination and the patient. Another way that a physician or practitioner who has never seen the patient in-person can refill a medication past the 30-day initial period via telehealth is if the virtual prescriber receives a referral from another DEA registered practitioner. Under this scenario, the patient must have received an in-person medical evaluation from the referring practitioner.

In addition, before prescribing buprenorphine via telehealth, physicians and other practitioners licensed to prescribe controlled substances must consult a prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP). If the practitioner is unable to consult a PDMP for some reason (if the PDMP is down or if the practitioner is unable to access it), the practitioner can only prescribe up to 7-days’ worth of medication until the practitioner is able to consult the PDMP.

In all, ACEP has strongly advocated for reducing barriers related to the treatment of OUD, so we do see this proposal as a step in the right direction. We agree with the DEA that “increasing patient access to medication for opioid use disorder is necessary to both prevent and ameliorate the catastrophic drug poisonings that are occurring as a result of fentanyl.”

The DEA is also proposing through another reg to allow similar telehealth flexibilities for non-narcotic schedule III-V controlled medications, using the authority of the Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act of 2008 ("Ryan Haight Act"). This Act, which is being implemented 15 years after its enactment (!!), attempts to prevent the illegal distribution and dispensing of controlled substances “by means of the Internet.” While the Ryan Haight Act generally requires that “the dispensing of controlled substances via the Internet” be based on a valid prescription involving at least one in-person medical evaluation, it also established certain exceptions that would allow prescriptions to be issued remotely without a prerequisite in-person visit.

The Ryan Haight Act was named for a California high school student who died in 2001 from a drug poisoning resulting from a controlled prescription medication he obtained from a rogue online pharmacy. That rogue online pharmacy allowed customers, like Ryan and others, to obtain controlled medications without an in-person medical evaluation by the prescriber. According to the DEA, in Ryan's case, and in many others, the "[e]ase of access to the Internet, combined with lack of medical supervision [...] led to tragic consequences in the online purchase of prescriptions for controlled substances."

Obviously, a lot has changed since 2008 when the law passed (and since 2001 when Ryan tragically died), but the DEA is still using the same authority and rationale embedded in the law for making its policy. With respect to the exceptions for the required prerequisite in-person visit, the DEA is specifically proposing to allow physicians and other practitioners with an active DEA license to initially prescribe non-narcotic schedule III-V controlled medications via telehealth without a prior in-person visit. For these medications, “telehealth” would be defined an audio-visual encounter, and there would be the same 30-day prescribing limit described above for buprenorphine. To continue prescribing to that patient, the prescribing practitioner would be required to examine the patient in person within 30 days. Alternatively, as described above, if the prescribing practitioner receives a telehealth referral for the patient, the practitioner may rely on the referring practitioner's in-person medical evaluation in order to prescribe the controlled substance via telehealth.

There are also strict record keeping requirements, including noting on the face of any telehealth prescription that the prescription had been issued based on a telehealth encounter. Finally, the same requirements described above around consulting PDMPs apply—or the prescription is limited to 7 days.

While these proposals are more constraining than the pandemic policies, here comes the major limitation that has already made telehealth advocates concerned about access: the DEA is proposing that telehealth would no longer be allowed for initially prescribing narcotics (with the exception of buprenorphine described above) or Schedule II medications. This means that certain pain medications like oxycontin or attention deficit disorder medications like Adderall could not be prescribed initially via telehealth and could only be prescribed virtually following at least one in-person medical examination. Other common medications listed out by schedule are found here.

There are some notable caveats and exceptions to the restrictive policies. First, it is important to reemphasize that the regs only affect patients who have never had an in-person encounter with the physician or practitioner who prescribes the controlled substance before. If a patient has received an in-person visit from the prescriber at any time, then the prescriber is allowed to provide prescriptions via telehealth after that. Further, if a patient established a virtual relationship with a physician or other health care practitioner during the COVID-19 PHE and received a controlled substance prescription via telehealth during that time, the DEA is allowing for a period of 180 days from the issuance of the final reg for the patient to receive an in-person visit. Further, veterans are allowed to be prescribed any controlled substance (including narcotics) via telehealth if the physician or practitioner who prescribes the medication is employed by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and the patient has received an in-person visit from that or another VA practitioner.

These proposed regs are a bit confusing, and the DEA tried to summarize the proposals in this table, summary, and diagram. I’ve also tried to lay out the major requirements in the below schematic:

The DEA chooses to be restrictive about initial telehealth prescriptions because of its overall concerns about diversion and improper use of medications. In the regs, the DEA points out that diversion of controlled substances, including buprenorphine, is dangerous and may lead to misuse and sometimes fatal drug poisonings. However, interestingly, the limited studies that the DEA uses to make its points about diversion predate the COVID-19 pandemic and do not take into account how the expanded access of telehealth during the PHE has actually affected diversion. One could make the argument that diversion could have actually decreased over the last three years as individuals who really needed medications were able to access them easier—and diversion could increase if access to medication becomes more difficult again.

ACEP will continue to review the regulations and assess their impacts on emergency physicians and your patients. It is important to note that these are only proposed regulations. The DEA is seeking comment on various aspects of the regs and will need to issue final regs (which hopefully take into account the comments) before any of the policies become effective.

Stay tuned for more updates as ACEP plans its response to these regs! And, until next week, this is Jeffrey saying, enjoy reading regs with your eggs!