Pediatric Pyloric Stenosis

Samuel H. F. Lam, MD, MPH, FACEP

I. Introduction and Indications

- Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is an idiopathic, acquired condition generally presenting at 2-12 weeks of age.

- Caused by hypertrophy of the circular muscle of the pylorus causing gastric outlet obstruction.

- Classic findings include projectile non-bilious vomiting, palpable “olive” at the epigastrium, and hypochloremic alkalosis which are present 97%, 13.6%, and 10% of the time, respectively.1

- Ultrasound is the gold standard in diagnosis, with sensitivity 97-100% and specificity 99-100% in the radiology literature.2

- In a prospective observational study of 67 patients, Sivitz et al found that point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) performed by trained emergency physicians has a 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity in diagnosing pyloric stenosis.3

- Case reports and series of emergency physicians using POCUS to diagnose pyloric stenosis have also been published.4,5

- While POCUS diagnosis of pyloric stenosis is usually not an emergency, it can help narrow down the differential diagnosis in a sick child and expedite disposition in resource-limited emergency departments.

II. Anatomy

Figure 1. Anatomy of the stomach and pylorus (D: Duodenum, GB: Gallbladder, P: Pylorus, S: Body of Stomach)

- Pylorus is at the distal end of the stomach.

- Generally lies medial to the gallbladder.

- Anterior and lateral to the aorta and superior mesenteric artery.

III. Scanning Technique, Normal Findings and Common Variants

- Typically, a high frequency (5-10MHz), linear/curvilinear transducer is used due to small size and superficial location of structures.

- Patient should be supine or right lateral decubitus which to facilitate antrum filling.

- Start scanning slightly to the right of epigastrium.

- Indicator to the patient’s right side with the probe held transversely on the abdomen.

- Graded compression to get rid of excessive bowel gas.

- Find the gallbladder adjacent to the liver and look medially to locate the pylorus.

- Alternatively, find the fluid-filled stomach and follow it distally to the pylorus.

- Figure 2. Sonographic anatomy of the pylorus (P) in relation to the gallbladder (GB) and stomach (St)

- Use the aorta/ superior mesenteric artery as additional landmarks if necessary (pylorus is anterior to them).

- Figure 3.Sonogaphic anatomy of the pyloric muscle (M) in relation to the aorta (Ao), superior mesenteric artery (SMA), and splenic vein (SV)

- Locate the hypoechoic pyloric muscle.

- Figure 4a. Long axis view of the pyloric musle (M) highlighted by white arrows at the distal end of the stomach (St)

- In between the pyloric muscles is the hyperechoic pyloric channel made up of gastric mucosa.

- Figure 4b.Highlighted pyloric channel made up of gastric mucosa

- On the short axis or transverse view, the pylorus has a “target” appearance

- Figure 5. Pylorus in short axis/ transverse view, the “target sign” (M: pylorus muscle)

IV. Pathology

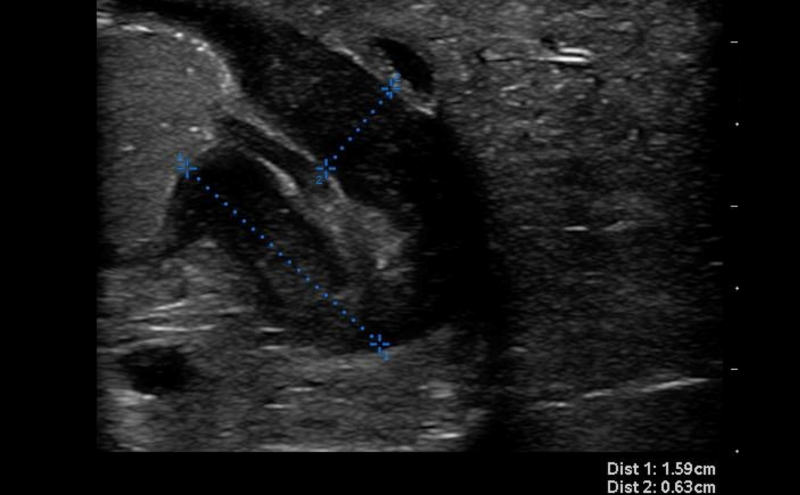

- Thickness of the pyloric muscle can be measured in the long or short axis view

- Figure 6. Hypertrophied pyloric muscle in long axis measuring 4.3mm

- Figure 7. Hypertrophied pyloric muscle in short axis measuring 5.5mm

- A thickness of ³3mm is considered abnormal or hypertrophied

- Some experts also advocate the measurement of pyloric channel length. Unfortunately, there is no agreement for a firm cutoff for normal. In general, anything over 18mm should be considered abnormal.

- Figure 8. Elongated pyloric channel (25mm) consistent with stenosis

- Poor gastric emptying is also an indicator of obstruction

- Prevalence of pyloric stenosis is 3/1000 live births

- Almost universally fatal if untreated

V. Pearls and Pitfalls

- Pearls

- Pylorus POCUS tends to be difficult to master because of relative rarity of the pathology, the small size of the pylorus muscle, and fact that more often than not the patient will be uncooperative.

- Warm gel can be less irritating to the infant.

- Take time for infant to get used to the transducer.

- Try feeding the child and follow the stomach contents as it moves through the pylorus.

- Pitfalls

- Imaging a tangential section of pylorus muscle can give false positive result.

- Overdistended stomach can displace the pylorus posteriorly and give false negative result.

- Pylorospasm can mimic stenosis. If uncertain about measurement, may repeat scan in 20 minutes to watch for passage of stomach content and change in measurements of pylorus muscle (return to normal values indicates pylorospasm).

VI. References

- Glatstein M, Carbell G, Boddu SK, et al. The changing clinical presentation of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: the experience of a large, tertiary care pediatric hospital. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2011;50:192-5.

- Hernanz-Schulman M. Pyloric stenosis: role of imaging. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39(Supp 2):S134-9.

- Sivitz AB, Tejani C, Cohen SG. Evaluation of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis by pediatric emergency physician sonography. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20:646-51.

- Malcom GE 3rd, Raio CC, Del Rios M, et al. Feasibility of emergency physician diagnosis of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis using point-of-care ultrasound: a multi-center case series. J Emerg Med. 2009;37:283-6.

- Dorinzi N, Pagenhardt J, Sharon M, et al. Immediate emergency department diagnosis of pyloric stenosis with point-of-care ultrasound. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2017;1:395-8.