Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm (AAA)

Zachary Risler, MD MPH, Anthony J. Dean, MD and Bon S. Ku, MD

I. Introduction and Indications

- Ultrasound is an ideal method for detecting AAAs due to its accuracy, low cost, and ability to be performed at the bedside.1,2,3

- Physical exam has a sensitivity of only 68% for detecting AAA.4

- Abdominal aortic imaging can be taught to novices and can be done at the bedside with hand-held devices.5,6

- Two separate studies by Kuhn et al. and Constantino et al. showed that emergency physicians can identify an AAA with 100% sensitivity and a specificity of 100% and 98%, respectively.7,8

- Reed and Cheung in a 2014 study demonstrated the importance of point of care ultrasound. In a study of 53 patients, 18 patients that had a point-of-care (POC) ultrasound (US) had an average time to diagnosis of 51 minutes vs 111 minutes in the patients that did not have immediate US.9

- Mortality rate after ruptured AAA approaches 90%.10

- Indications include presence of syncope, shock, hypotension, abdominal pain, abdominal mass, flank pain, or back pain, especially in the older population.11

II. Anatomy

- Abdominal aorta lies slightly to left of midline and bifurcates at the level of the 4th or 5th lumbar vertebral body. (Illustration 1) The surface anatomy landmarks are the xiphoid process and the umbilicus (Illustration 2).

- Illustration 1. Overview of the abdominal aorta with major branches (Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aorta_branches.jpg)

- Illustration 2. Scanning technique. Probe is just inferior to the xiphoid process, indicator towards the patient’s right (star) for a transverse view. Probe is moved inferior to the umbilicus.

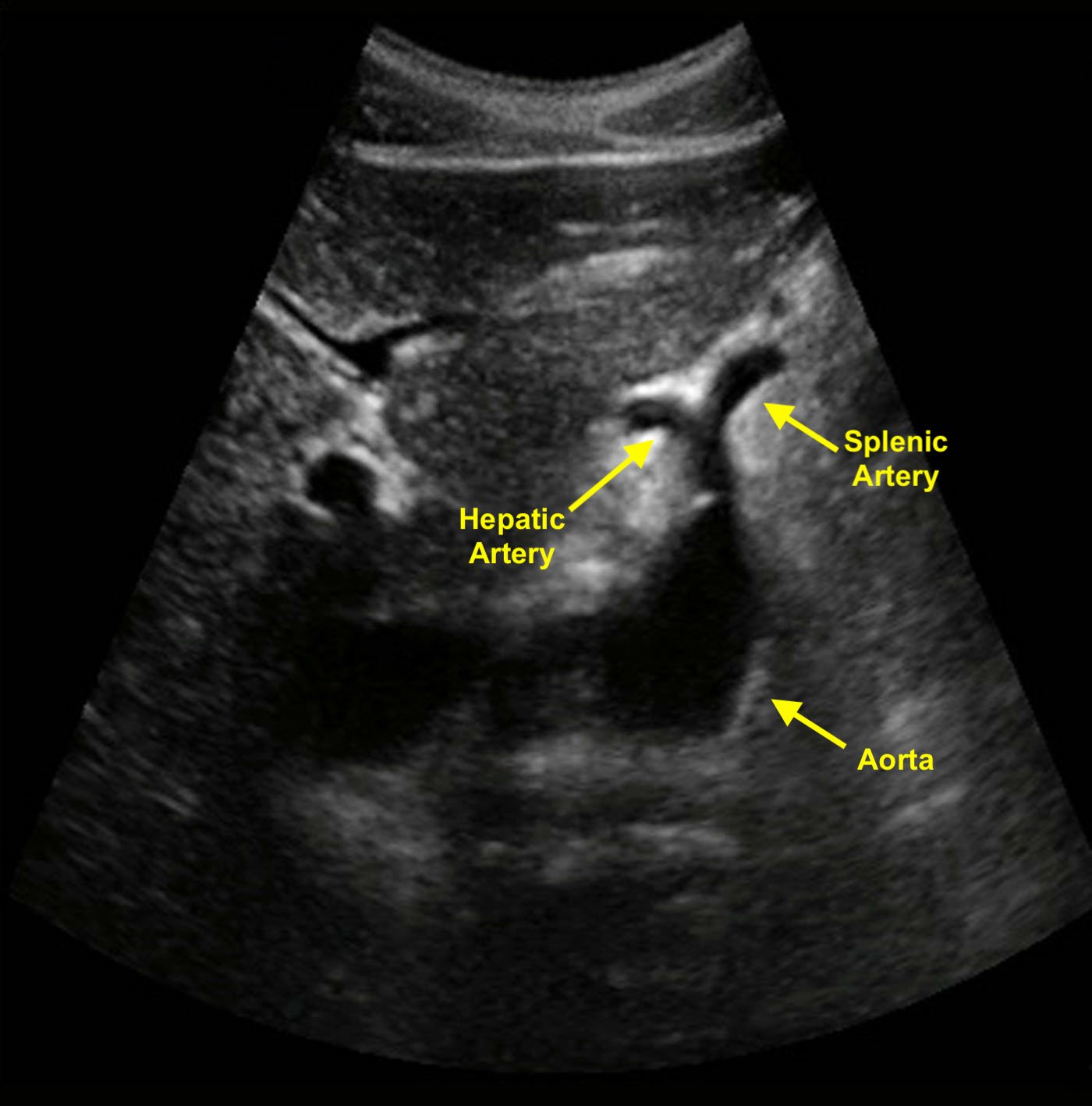

- Celiac trunk is first major vessel to arise from the abdominal aorta in the midline anteriorly (Figure 1). This short vessel can often be seen in the transverse plane, dividing in a “wide Y.” This sonographic view is known as the “seagull sign.”

- Fork on patient’s right is common hepatic artery.

- Fork on patient’s left is splenic artery.

- Figure 1. Transverse image of the aorta shows a classic example of the seagull sign. The celiac trunk branches into the hepatic and splenic arteries.

- About 1 cm inferior to the celiac trunk arises the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). Renal arteries arise on either side 1cm below SMA. Although these cannot be seen on a sagittal view of the aorta, they can sometimes be identified with careful transverse scanning.

- In long axis the SMA can be found running parallel to the aorta.

- Figure 2. Aorta imaged in long axis with the celiac trunk and SMA branches

- The aorta moves anterior as it courses distally.

III. Scanning Technique, Normal Findings and Common Variants

Sonographic Technique

- 5 MHz transducer is adequate for most abdominal scanning, including aorta. Lower frequency may be needed in large patients, and higher frequency will give more detail in thin patients.

- Aorta and iliac arteries are measured from outer wall to outer wall. Normal abdominal aorta diameter is less than 3 cm. AAA is defined as greater than 3 cm.

Start in transverse plane, high in the epigastrium, using liver as a sonographic “window.” Identify the vertebral body (a dark, rounded shape, with dense shadow)

- Identify aorta on the patient’s left, and the inferior vena cava (IVC) on the patient’s right anterior to vertebral body.

- In real-time obtain transverse clips of the aorta from the celiac to the bifurcation.

Video 1. Transverse sweep of normal aorta from proximal to iliac artery bifurcation - Rotate the probe’s pointer clockwise to the 12 o’clock position for sagittal clips from the celiac to the bifurcation.

- At least 3 transverse views, labeled, “proximal”, “mid”, “distal” with calipers should be recorded. One view should show the maximal aortic diameter.

- Proximal measurements should be obtained around the celiac trunk or liver tip.

- Figure 3. Transverse view of the proximal aorta

- Mid measurements should be obtained below the SMA branch point.

- Figure 4. Transverse view of the mid aorta

- Distal measurements should be obtained above the bifurcation.

- Figure 5. Transverse view of the distal aorta

- Proximal measurements should be obtained around the celiac trunk or liver tip.

- Obtain views of the iliac arteries if possible. Normal measurements should be less than 2.0 cm.

Video 2. The aorta bifurcates into the iliac arteries

Special Techniques for Ultrasound Evaluation

The transverse colon should be expected to be encountered running across the upper abdomen immediately inferior to the liver edge. It is usually fairly wide and filled with gas. In order to obtain complete exam of the aorta without “skipped areas” it may require separate views from above (with the transducer directed inferiorly, using the liver as a window) and below, with the probe fanning in a cephalad direction. At any location, if bowel gas makes it difficult to obtain images, some or all the following can help:

- Apply gentle downward pressure, known as graded compression. It may take 1-2 minutes of compression to allow bowel to move aside.

- Move the probe slightly off midline and angle towards midline.

- Reposition patient in the right decubitus position.

- Obtain right coronal views using the liver as a window (Figure 6). The probe is placed with indicator towards patient’s head, position in mid axillary line at or below costal margin, directed slightly anterior. In most patients this only affords very limited views of the upper aorta, and it is technically challenging. In cases where it is possible, the IVC and aorta can be seen running parallel, one in front of the other with the aorta lying “deep” on the screen to the IVC.

- Figure 6. Probe positioning for visualization of the aorta from the right upper quadrant

Video 3. The IVC and aorta visualized through the liver in the right upper quadrant - Try imaging from below the umbilicus with the probe directed cephalad.

- Try imaging the aortic bifurcation from an oblique angle with the probe placed lateral to the umbilicus (usually to the patient’s left) and pointing towards midline. Occasionally imaging from below the umbilicus will afford views of the bifurcation.

IV. Pathology

- AAA is described as being a focal dilatation of the abdominal aorta of 150% of normal.12-13 Although there is no established definition of aneurysm size, conventionally, an AAA is diagnosed when the diameter exceeds 3.0 cm.14

- Figure 7. Transverse view of a 4.1 cm AAA

Video 4. Transverse view of large AAA

Video 5. Longitudinal view of large AAA - Risk of rupture for AAA of 3.0 cm is less than 4% over 5 years; this risk, however, substantially increases for AAA’s with larger diameters.15

- The majority of aneurysms are fusiform, affecting the entire circumference of the vessel. Saccular aneurysms are less common and affect only part of the aortic circumference, and may occur in any direction, usually anteriorly or laterally. This makes them much easier to miss if areas of the aorta are “skipped” in the exam.

- 90% of all AAA’s will occur distal to the renal arteries, termed infra-renal.

- Treatment of AAA is entirely surgical.

- Iliac artery aneurysm is outside of the purview of emergency medicine and bedside ultrasound but if noted to be larger than >1.85 cm for a man and >1.5 cm for a woman, appropriate follow-up should be organized as significant risk of rupture and death are associated with isolated iliac artery aneurysm.16

- Figure 8. Iliac artery aneurysm

V. Pearls and Pitfalls

- The only contraindication of scanning for AAA is delay to surgical intervention.

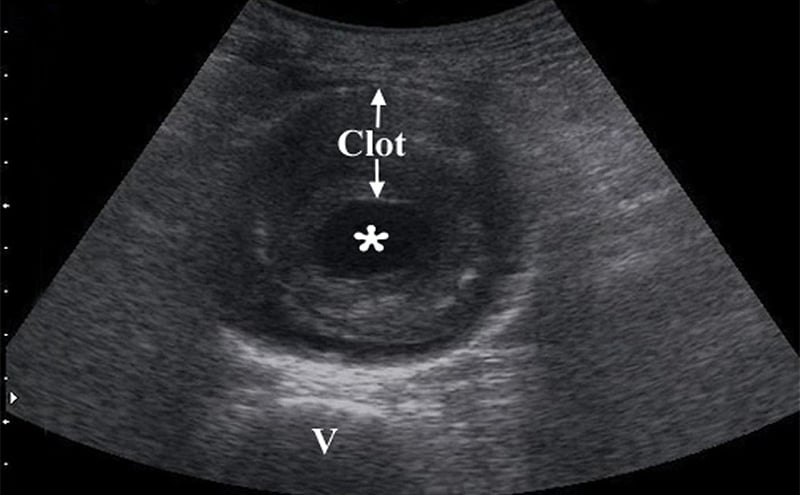

- Obtain measurements of aorta from outer wall to outer wall. Since aneurysms will often contain a thrombus, and with time this becomes calcified and hyperechoic, one may accidentally mistake the inner rim of the thrombus for the aortic wall. Doing this will lead a falsely decreased measurement of the true aortic diameter, possible causing the aneurysm to be missed completely.

- Figure 9. Transverse view of a 7 cm AAA with intraluminal clot (* on the lumen, “v” denotes vertebral body)

- The attempt should be made to create transverse cuts with respect to the aorta, even when it is tortuous, ectatic and deformed by advanced atherosclerosis. In such circumstances, any single longitudinal image will not be complete, and will section parts of the vessel obliquely. In such vessels, any view can both overestimate and underestimate the size of the vessel.

- A small aneurysm does not preclude rupture:17,18 Any symptoms consistent with aortic pain in a patient with an aortic diameter greater than 3.0 cm should have this diagnosis (or alternative vascular catastrophes) ruled out.

- Do not mistake the IVC for the aorta. It is important to identify the branches of the aorta. The IVC will run through the liver with the hepatic vein draining into it. You can also identify the IVC entering into the right atrium (Figure 9).

- Figure 10. Note the difference between the aorta and the IVC

- Scanning should be systematically performed in real-time from the diaphragmatic hiatus to the bifurcation in order to avoid missing small, localized saccular aneurysms.

- As in any POCUS study, do not become over reliant on limited imaging.

VI. References

- Wilmink AB, Quick CG. Epidemiology and potential for prevention of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Brit J Surg.1998;85:55–62.

- S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: recommendation statement. Ann Int Med. 2005;142(3):198-202.

- Hermsen K, Chong WK. Ultrasound evaluation of abdominal aortic and iliac aneurysms and mesenteric ischemia. Radiol Clin N Am. 2004;42:365-81.

- Fink HA, Lederle FA, Roth CS, et al. The accuracy of physical examination to detect abdominal aortic aneurysm. Arch Int Med. 2000;160(6):833-6.

- Lin PH, Bush RL, McCoy SA, et al. A prospective study of a hand-held ultrasound device in abdominal aortic aneurysm evaluation. Am J Surg. 2003;186(5):455-9.

- Riegert-Johnson DL, Bruce CJ, et al. Residents can be trained to detect abdominal aortic aneurysms using personal ultrasound imagers: a pilot study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18(5)394-7.

- Kuhn M, Bonnin RL, Davey MJ, et al. Emergency department ultrasound scanning for abdominal aortic aneurysm: accessible, accurate, and advantageous. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36(3):219-23.

- Constantino TG, Bruno ED, Handly N, et al. Accuracy of emergency medicine ultrasound in the evaluation of abdominal aneurysm. J Emerg Med. 2005;29:455-460.

- Reed MJ, Cheung L. Emergency department led emergency ultrasound may improve the time to diagnosis in patients presenting with a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2014; 21(4):272-275.

- Ernst CB. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. N Engl J Med.1993;328:1167-72.

- American College of Emergency Physicians. Ultrasound guidelines: Emergency, Point-of-care, and clinical ultrasound guidelines in medicine [policy statement]. Approved April 2023.

- Johnston KW, Rutherford RB, Tilson MD, et al. Suggested standards for reporting on arterial aneurysms. Subcommittee on reporting standards for arterial aneurysms, Ad Hoc committee on reporting standards, Society for Vascular Surgery and North American Chapter, International Society of Cardiovascular Surgery. J Vasc Surg. 1991;13:444–50.

- Sox HJ, Huber JM (eds.) Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, Second Edition, Section I, Chapter 6. Copyright©, Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center.

- Sakalihasan N, Limet R, Defawe OD. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Lancet. 2005;365:1577-89.

- Vardulaki KA, Prevost TC, Walker NM, et al. Growth rates and risk of rupture of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1674-1680.

- Bacharach JM, Slovut DP. State of the art: management of iliac artery aneurysmal disease. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2008; 71:708.

- Miller J, Grimes P, Miller J. Case report of an intraperitoneal ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm diagnosed with bedside sonography. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6(6),661–4.

- Darling RC, Messina CR, Brewster DC, et al. Autopsy study of unoperated abdominal aortic aneurysms. Circulation. 1977;56(3) Supp II:161-4.