Bridging distances with tele-ultrasound: a potential solution to scaling up use of point-of-care ultrasound within emergency care settings

David A. Martin, MD

Andrea Dreyfuss, MD, MPH

University of Minnesota/Hennepin Department of Emergency Medicine

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) has become an essential competency for emergency care providers, particularly those working in resource-constrained settings where timely access to laboratory and diagnostic testing is unavailable.1,2 Although emergency medicine is an established medical subspecialty in multiple Latin American countries, residency training in POCUS varies from country to country and is limited due to lack of access to expert educators and educational resources.

We first became aware of the need for POCUS education in December of 2015 while teaching at a Peruvian conference on emergency medicine and disasters. We realized that creating sustainable change would require more than just teaching basic POCUS skill sets. We needed to help create POCUS leaders and champions who themselves could become educators. This meant we had to choose people based on their capability to achieve this and have a level of training that went beyond implementation alone.

Therefore, in 2018, we established the first year-long ultrasound point-of-care ultrasound fellowship for emergency medicine physicians in Peru. Given the inherent limitations posed by geographical distances, we opted to design a curriculum which incorporated the use of tele-ultrasound enabled handheld portable devices to augment in-person hands-on education. We were able to design a year-long POCUS fellowship modeled on the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) fellowship guidelines that incorporated traditional in-person hands-on learning in Lima and at our academic institution in the United States with both real-time tele-ultrasound and educational teleconferences broadcasted weekly between our US and Peruvian fellowship training site.3

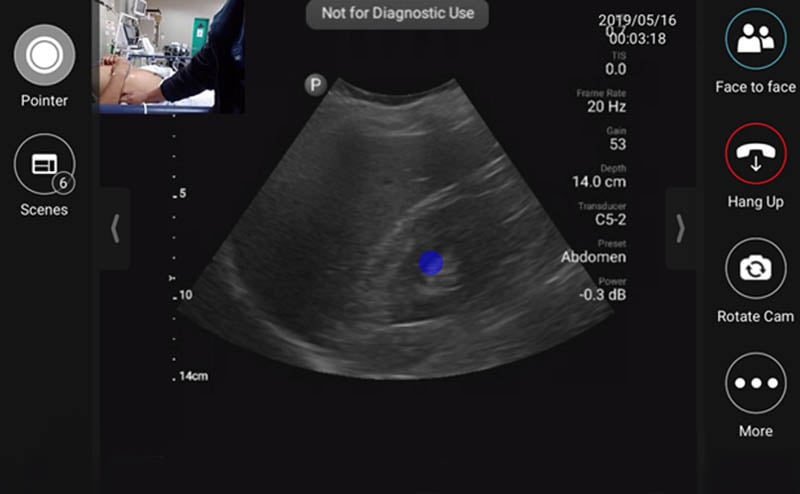

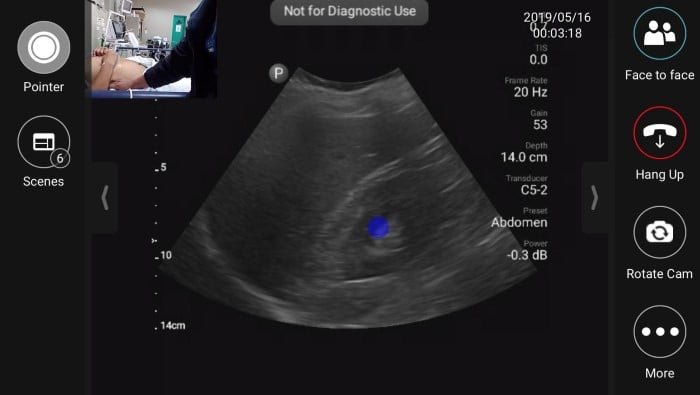

Figure 1. Tele-ultrasound platform as visualized by remote user providing diagnostic/procedural assistance

Figure 1. Tele-ultrasound platform as visualized by remote user providing diagnostic/procedural assistance

During the initial months of the fellowship, onsite support during the fellow’s scanning shifts was provided by volunteer visiting instructors from the US. Following this initial period, visiting instructors were not always present in Lima, however fellows could utilize the built-in tele-ultrasound software on the handheld ultrasound device to contact a pool of on-call physicians during their required ultrasound scanning shifts. The inaugural year of the fellowship we primarily relied on tele-ultrasound to provide live support during the fellow’s self-directed scanning shifts whenever questions arose.

In 2020, year three of the fellowship, we were forced to adapt to strict travel restrictions enforced due to the COVID-19 pandemic. We suddenly were forced to rely primarily on tele-ultrasound to provide ongoing teaching and support. We shifted from utilizing tele-ultrasound on an as needed basis to scheduling tele-ultrasound scanning shifts accompanied by a senior ultrasound fellowship trained instructor located either in the US or Peru. An added benefit of having graduated five classes of fellows to date is that we can now rely on former fellowship graduates to host tele-ultrasound sessions with the new class of fellows.

For our second-year fellowship class we were able to expand from our primary training site in Lima to three additional sites: one in Lima, one in Cusco and one in Iquitos. For our third-year class we for the first time expanded outside of Peru, with a fellow in Costa Rica. This would not have been possible without tele-ultrasound. In fact, we met our Costa Rican fellow on her graduation for the first time in person due to COVID-19 travel restrictions. Despite this limitation our Costa Rican fellow was able to continue to learn and hone both her ultrasound knowledge and image acquisition skills in lock step with her colleagues who were in Lima and have had access to in-person, hands-on support. She is now the fellowship director and has trained two other fellows and is in fact expanding withing Costa Rica to two different more remote sites. Our fellowship now in its 6th year is training 14 fellows in five different countries in Latin America.

Our experiences add to the body of growing literature in support of the use of tele-ultrasound for providing remote training and support. A letter to the editor published in the Critical Care Explorations journal described the use of tele-ultrasound to minimize potential risk of exposure to COVID-19 patients undergoing central line placement.4 Another recently published study showed no inferiority between traditional in-person versus remote learning when teaching ultrasound-naïve medical students.5 The use of tele-ultrasound is therefore a promising potential solution for providing the ongoing support needed to develop and maintain POCUS fellowship training programs in areas where there is limited access to expert POCUS educators, both domestically and in international settings.

References

- Ultrasound guidelines: emergency, point-of-care and clinical ultrasound guidelines in medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69(5):e27-e54.

- Lutz H, Buscarini E, World Health Organization, eds. Manual of Diagnostic Ultrasound. 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2011.

- Dreyfuss A, Martin DA, Farro A, et al. A Novel Multimodal Approach to Point-of-Care Ultrasound Education in Low-Resource Settings. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(4):1017-1021.

- Gibson LE, Low SA, Bittner EA, Chang MG. Ultrasound Teleguidance to Reduce Healthcare Worker Exposure to Coronavirus Disease 2019. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2(6):p e0146

- Drake AE, Hy J, MacDougall GA, et al. Innovations with tele-ultrasound in education sonography: the use of tele-ultrasound to train novice scanners. Ultrasound J. 2021;13(1):6.