Acute Mitral Regurgitation in the Emergency Department

Joshua M. Jacquet, MD, RDMS, FACEP, AEMUS FPD

Brian Makowski, DO

Lorne Strausbaugh, DO

Cleveland Clinic Akron General

Case Presentation

A 56-year-old female with history of hyperlipidemia, mild mitral regurgitation, and type 2 diabetes presents to the emergency department for 5 days of diffuse chest pain with dyspnea, lower extremity edema, palpitations and fatigue, all acutely worsening today.

On arrival, patient is noted to have mottled skin and appears tachypneic and unwell. Initial vital signs include temperature 36.8C, BP 82/56, HR 127 bpm, RR 30, and SpO2 86% on room air. Patient was placed on 4L nasal cannula and given 500 cc of LR with mild improvement. Physical exam is notable for bilateral crackles in the lung bases with pitting edema in the lower extremities. EKG was reviewed which showed sinus tachycardia with some T wave inversions in the inferior leads.

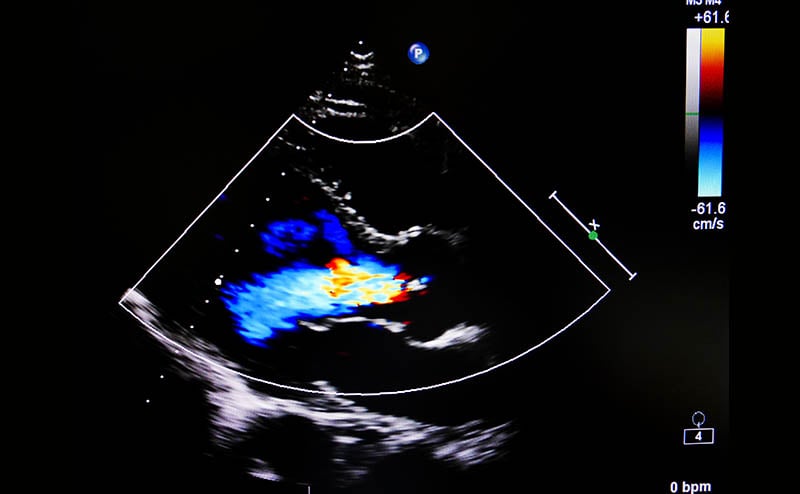

A point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) was performed while awaiting lab results. The lung ultrasound showed bilateral diffuse B lines without a focal consolidation concerning for pulmonary edema. A focused cardiac ultrasound showed qualitatively normal left ventricular ejection fraction and left ventricular size.

Laboratory workup was notable for leukocytosis with WBC 14, glucose 455, HCO3 17, lactate 2.9, elevated creatinine from baseline at 1.6, and mildly elevated high sensitivity troponins. A chest x-ray was concerning for pulmonary edema with bilateral patchy opacities – consistent with earlier POCUS.

Background

Acute severe mitral regurgitation (MR) is a medical and surgical emergency. Rapid identification is critical as its presence has significant hemodynamic consequences and requires multidisciplinary care for stabilization and definitive management with surgical repair or replacement. Patients with acute MR can present with a range of symptoms including acute respiratory failure from pulmonary edema and/or cardiogenic shock. Acute MR also shares similar clinical features to other cardiopulmonary conditions, and often is initially diagnosed generally as decompensated heart failure without recognizing the underlying valvular etiology. History and physical exam findings can be subtle, with approximately 50% of patients with moderate to severe acute MR having no audible cardiac murmur.1

POCUS provides emergency department physicians a powerful diagnostic tool in the evaluation of the acutely dyspneic patient and the patient in cardiogenic shock. 2D B-mode and Color Flow Doppler are the backbone for evaluation of a suspected valvular lesion, with additional Continuous-Wave Doppler and Pulsed-Wave Doppler techniques available for further assessment of regurgitant flow if present. Although the evaluation of MR with comprehensive transthoracic echocardiography by cardiology can be time consuming and nuanced, a simplified approach in the evaluation of valvular disasters can be successfully implemented within the ED by the point-of-care provider.2

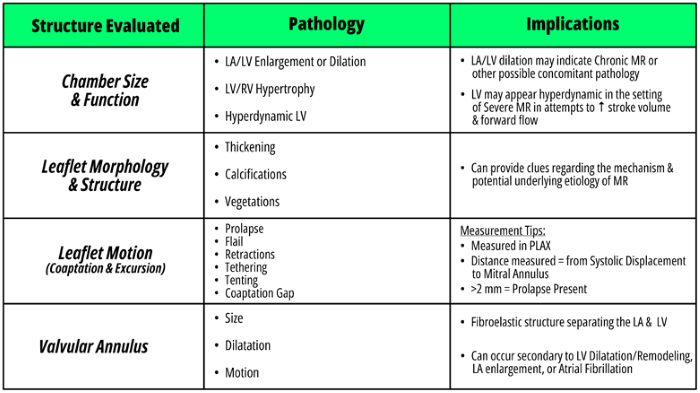

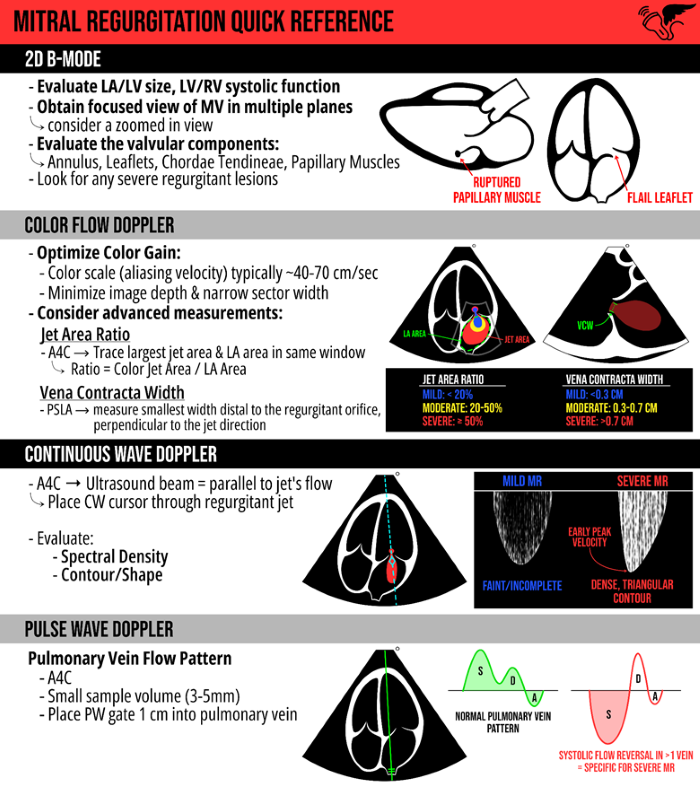

The ED Valvular POCUS exam begins with 2D B-mode in typical fashion evaluating overall left and right chamber size/function, as pathologies, or lack of, can aid in delineating etiology and chronicity of an underlying regurgitation lesion.

Closer inspection of the valvular apparatus and leaflets can then be performed, screening for visible pathologies that may provide hints to the presence, severity, and possible etiology of underlying MR (Table 1). A focused view of the mitral valve can be obtained through use of zoom functions, and ensuring to always assess the valve in multiple different planes of imaging, specifically the parasternal long-axis (PLAX) and apical four-chamber (A4C) views. When evaluating cardiac leaflets, assess the morphology, coaptation and motion of the leaflets

Table 1. 2D B-mode evaluation and potential pathology in mitral regurgitation

Table 1. 2D B-mode evaluation and potential pathology in mitral regurgitation

Throughout the 2D exam, close attention for pathology leading to severe regurgitation should be sought, as these have been found to have a high specificity and positive-predictive value for the presence of acute severe MR (Figure 1).3 It is important to note though that absence of these lesions does not rule out severe MR.

Figure 1. Severe regurgitant lesions associated with severe, acute MR

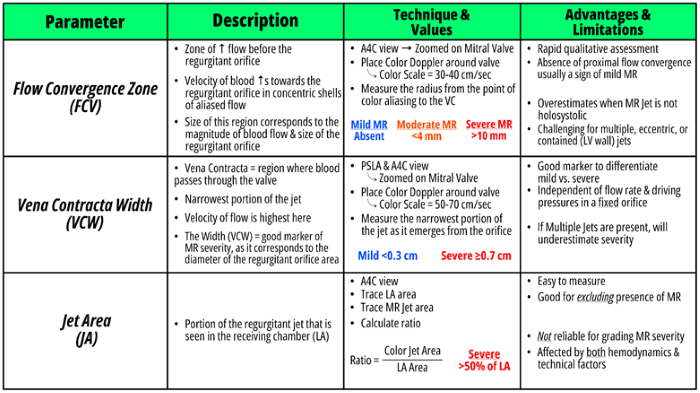

Color Flow Doppler (CFD) evaluation can then be performed, and is the most essential component of the valvular assessment. CFD can not only diagnose MR by discovering the presence of a regurgitant jet, but also help in determining its mechanism, severity, and hemodynamic impact. Once a regurgitant jet is identified, evaluate the jet’s three main components and direction of flow. Jet direction consists of three categories: central, eccentric, and multiple jets. In the presence of a flail leaflet, the regurgitant jet is typically located opposite to the affected leaflet (anterior flail leaflet = posterolateral jet, posterior flail leaflet = anteromedial jet). Presence of an eccentric jet should be considered severe until proven otherwise, and should alert you to the possibility of structural abnormalities.2 Multiple jets in unpredictable directions are often seen in patients with endocarditis.

Qualitative measurements of the jet consist of the proximal flow convergence (PFC), vena contracta width (VCW), and jet area (JA) (Table 3). Although measurement of these parameters may be considered out of the realm of the average POCUS user, it is feasible to recognize the main values concerning severe MR, which include a jet area of >50% of the LA and a VCW of >0.7 cm. Further details on technique, limitations, and benefits of these parameters can be found in Table 2.

Table 2. Qualitative parameters evaluated in mitral regurgitation

Table 2. Qualitative parameters evaluated in mitral regurgitation

While the majority of semi-quantitative and quantitative assessments are outside the scope of this discussion, a few Continuous-Wave Doppler (CWD) and Pulsed-Wave Doppler (PWD) measurements are relatively easy and feasible to perform by an ED POCUS user. CWD can be applied through the regurgitant jet, and the resulting spectral waveform is analyzed for its contour and density. A parabolic/round shape is typically found in mild-to-moderate MR, and triangular/truncated contour with early peaking denoting a more severe and hemodynamically significant regurgitant jet. Faint, partial or incomplete waveforms can be seen in mild-to-moderate MR, whereas waveforms in severe MR will have a dense, holosystolic appearance.

PWD of pulmonary venous flow can be used to provide additional information of the severity and hemodynamic consequences of MR as well. Normal doppler tracing of pulmonary venous flow shows an upward deflected systolic wave (S-wave), then a smaller, upward deflected diastolic wave (D-wave), and is finally ended with a downward deflection which represents atrial contraction (A-wave). In severe MR, a systolic flow reversal pattern (downward deflecting S-wave), has been shown to be specific for severe MR.2 It is much more specific for severe MR if more than one pulmonary vein displays systolic flow reversal, but if technically challenging to get multiple satisfactory pulmonary vein waveforms via a transthoracic approach. Further details on CWD & PWD techniques and measurements can be found in Figure 2.

Case Resolution

The patient continued to demonstrate symptoms and vitals consistent with shock. Given concern for fluid overload without clear etiology, further investigation was done with point-of-care cardiac ultrasound by a more experienced practitioner while awaiting comprehensive echocardiography. This showed left atrial dilation but again normal LV size and function. Color flow doppler was applied, showing a posterolateral eccentric MR jet. On acquisition of higher quality images, a flail leaflet could be visualized. Review of further records showed a TTE from ~2 years ago quantifying the patient’s mitral regurgitation as mild. Consultation with cardiology at the time had revealed mitral annular calcification as the suspected etiology.

Further fluid resuscitation was deferred and the patient was started on epinephrine drip for a MAP goal of 65. The cause of shock was suspected valvular cardiogenic at this time given the focused cardiac ultrasound findings, but a broad differential remained including infectious and ischemic etiology, given the patient’s combination of symptoms and imaging/laboratory findings.

Cardiothoracic surgery was consulted for suspected acute mitral regurgitation causing cardiogenic shock, who planned for temporary mechanical support and subsequent mitral valve replacement pending clinical course. A heparin drip was considered for suspected NSTEMI in the setting of elevated high sensitivity troponin T’s. Broad spectrum antibiotics were started in case sepsis and pulmonary infection were contributing to shock and respiratory failure. The patient was admitted to the cardiovascular intensive care unit, where they required continued pressor support and was transitioned to NIPPV. Patient improved with inotrope support, NIPPV, diuresis and mechanical support. The diagnosis of flail leaflet and worsened MR was confirmed with a trans-esophageal echo, and the patient ultimately received mitral valve replacement.

Discussion

This was a case of acute mitral regurgitation as a result of spontaneous chordal rupture leading to flail leaflet, secondary to degenerative changes. This patient had a history of mild mitral regurgitation which worsened acutely in the setting of spontaneous rupture. Acute mitral regurgitation can occur secondary to various pathologies, the most common of which are endocarditis, congenital defects, mitral valve prolapse (possibly from myxomatous heart disease, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or ischemia), papillary muscle rupture (commonly from MI), chordae tendinae rupture (commonly from rheumatic heart disease).

When POCUS findings concerning for acute, severe MR are identified, this should trigger critical actions of obtaining comprehensive echocardiography and consultations with cardiology and cardiothoracic surgery.

Management strategies of acute, severe MR can be roughly classified into two categories of cardiogenic shock: “Cold & Wet” and “Warm & Wet.”

In “Warm & Wet”, patients will have signs of volume overload/pulmonary edema (“Wet”), with adequate cardiac output and perfusion (“Warm”). Management in this group is focused on preload and afterload reduction to reduce flow into LA and improve cardiac output. Medications such as nitroglycerin can be used, as when used at high doses it provides arterial vasodilation that can be titrated to decrease afterload as tolerated by patients blood pressure to maintain adequate perfusion. Additional benefit from nitroglycerin can include decreased preload from venodilation in these patients at lower doses. Other arterial dilators that can be considered for this class of patients include dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers. Dysrhythmias are not well tolerated in patients in cardiogenic shock, and prompt treatment/termination of them may be needed.

In “Cold & Wet,” patients similarly demonstrate signs of volume overload, however have reduced cardiac output and evidence of poor perfusion (“Cold”). These patients intuitively also have a much higher mortality rate. Treatment is centered around protecting circulation/mean arterial pressures (MAP) to provide adequate perfusion to coronary & end-organ perfusion. Pressors in this use case should be those that provide primarily inotropic support, such as epinephrine or norepinephrine, as vasoconstrictors could be harmful considering the changes in afterload. Other agents that could be considered, but likely less helpful considering side effect profile, would be dobutamine and milrinone. Digoxin additionally has inotropic properties and the added benefit of preventing dysrhythmias, and could be considered as an adjunct.

Common management strategies between these groups include proper respiratory support and termination of underlying dysrhythmias. Respiratory support is often centered around the use of non-invasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV). NIPPV helps decrease afterload, preload, and been shown to reductions in need for intubation and mortality in several studies (*RECAP). Intubation in cardiogenic shock places patients at high risk for hypotension and cardiac arrest, thus great effort should be taken to avoid. If intubation is inevitable, initiate NIPPV early and resuscitate as much as possible before performing.

Summary

Acute mitral regurgitation is a true time sensitive emergency often presenting as undifferentiated dyspnea and shock, and has a number of different etiologies including ischemic, infectious, myxomatous, and degenerative among others. This can be difficult to diagnose without the aid of ultrasound in the emergency setting. In the acute setting this will often appear as normal left atrial and left ventricular size on POCUS, perhaps with even hyperdynamic LV function. Thus, a bedside echo can be useful to assess for qualitative measures, including:

- Flail leaflet

- Ruptured papillary muscle

- Coaptation gap

- Color Flow Doppler to assess for regurgitant jets

- or more advanced techniques, such as CWD waveform evaluation, PWD tracing patterns and quantitative methods.

Once acute MR is recognized, management should be tailored to the patient ‘subtype,’ but overall include early specialist consultation, respiratory support with NIPPV, avoidance of dysrhythmias, tailored pressor support with primarily inotropic agents, and preload/afterload reduction as necessary.

Figure 2. POCUS quick reference for the evaluation of mitral regurgitation

Figure 2. POCUS quick reference for the evaluation of mitral regurgitation

References

- Otto CM. Acute Mitral Regurgitation in Adults. UpToDate. March 2022. Accessed at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/acute-mitral-regurgitation-in-adults?search=Acute%20mitral%20regurgitation%20in%20adults&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1%7E82&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H7

- Zoghbi WA, Adams D, Bonow RO, et al. Recommendations for Noninvasive Evaluation of Native Valvular Regurgitation A Report from the American Society of Echocardiography Developed in Collaboration with the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2017;30(4):303-371. Accessed at: https://www.asecho.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/2017VavularRegurgitationGuideline.pdf

- Chardoli M. Valvular Emergencies Part 1: Diagnosis and Management of Severe Mitral Regurgitation Made Easy! September 2023. Accessed at: https://recapem.com/valvular-emergencies-part-1-diagnosis-and-management-of-severe-mitral-regurgitation-made-easy-2/#MEDIAAF

- Naidu SS, Baran DA, Jentzer JC, et al. SCAI SHOCK Stage Classification Expert Consensus Update: A Review and Incorporation of Validation Studies: This statement was endorsed by the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), American Heart Association (AHA), European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Association for Acute Cardiovascular Care (ACVC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT), Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), and Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) in December 2021. JACC. 2022;79(9):933-946. Accessed at: https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.01.018

Additional Resources

Valvular Emergencies Part 1: Diagnosis and Management of Severe Mitral Regurgitation Made Easy! https://recapem.com/valvular-emergencies-part-1-diagnosis-and-management-of-severe-mitral-regurgitation-made-easy-2/#MEDIAAF

EMCrit 321 – CV-EMCrit – Acute Valve Disasters – Critical Aortic & Mitral Regurgitation and Bonus: VSDs with Trina Augustin https://emcrit.org/emcrit/valve-disasters-regurg/