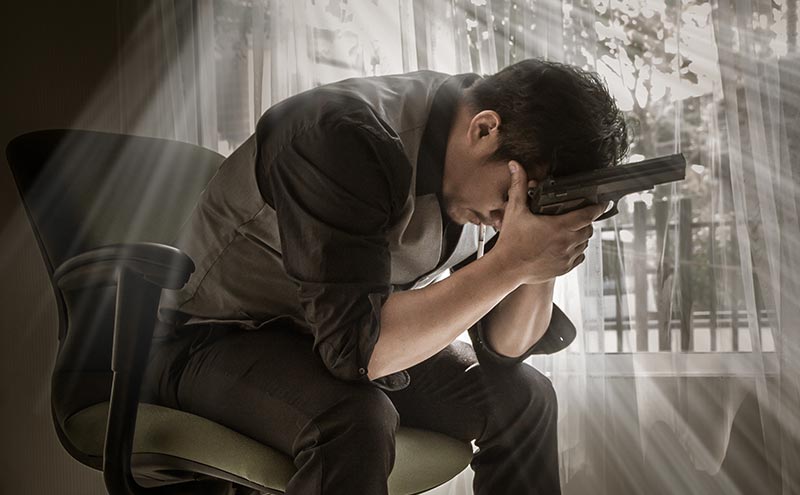

Firearms and Suicide

September is National Suicide Prevention Awareness month, a much-needed opportunity to shed light on and reduce stigma about a leading cause of death. While violent death rates have declined overall since the 1990s, suicide rates appear to be rising, and suicide is now the 10th leading cause of death in the United States.1 Suicide prevention requires a comprehensive strategy incorporating identification and intervention across the life span, and emergency physicians know just how difficult it can be to determine an individual patient’s risk for imminent self-harm.

One recommended aspect of ED care of suicidal patients is “lethal means counseling” – talking with patients (and their families) about reducing access to firearms, toxic medications, and other lethal methods of suicide.2 Discussing firearm access is of particular importance,3 given the high lethality of firearm suicide attempts (~85% case fatality rate)4 and the fact that firearms accounted for half of the 42,773 suicide deaths in the United States in 2014.5 Multiple studies have shown that a firearm in the home increases the risk of suicide, likely because of the impulsivity of many attempts combined with the lethality of guns.4 The goal of discussions about lethal means access is not to involve police or other authorities to confiscate firearms – rather, it is to encourage at-risk patients and families to lock up firearms or store them away from the home so that the at-risk person doesn’t have access.

Ideally, such conversations would begin long before a patient is seen in an ED for suicidal thoughts or behaviors. New partnerships between public health professionals and firearm retailers aim to encourage gun owners to recognize the risk factors and warning signs of suicide and make sure firearms are inaccessible to those at risk. The first such “Gun Shop Project” was in New Hampshire,6, 7 and similar programs have spread to states across the United States.8 Most programs involve posters and brochures in gun shops, along with education for gun shop or range employees about warning signs for suicide. In August 2016, the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and the National Shooting Sports Foundation (the trade association for the firearm industry in the United States) announced a partnership to expand these efforts nationwide, beginning with a pilot in Alabama, Kentucky, Missouri and New Mexico.9 In Colorado, our program has also explored other venues for educating firearm owners about suicide prevention, including presentations at gun shows and at a “Ladies’ Night” at a local gun shop.10

Work in this area is rapidly growing and changing, with many important, unanswered questions.11 How do collaborative efforts for suicide prevention with firearm retailers inform – or potentially undercut – efforts to reduce firearm injuries and deaths from other causes (including gang, youth, domestic and mass violence)? How effective are “Gun Shop Projects” or ED-based provider counseling in changing home firearm storage and, ultimately, reducing firearm suicides? Does counseling about locked firearm storage undermine messages that the safest home is one without a firearm,12 or is it somewhat analogous to tiered counseling about teen pregnancy—that is, abstinence is the only way to prevent all pregnancies, but contraception is the next best method? How can we, in the injury prevention and treatment community, coordinate and optimize our various strategies?

Hopefully, the coming years will see increasing collaboration within the injury prevention community and with community stakeholder groups, including firearm retailers and organizations. In 2014, 63% of the 33,599 firearm deaths in the United States were suicides.5 If we want to prevent suicides, we need to talk about firearms, and if we want to prevent firearm injuries and deaths, we need to talk about suicide.

- Understanding Suicide: Fact Sheet: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015 [cited 2015 July 30]. Available from: Learn More Here.

- Capoccia L, Labre M. Caring for adult patients with suicide risk: A consensus-based guide for emergency departments. Waltham, MA: Education Development Center, Inc., Suicide Resource Prevention Center, 2015.

- 10 Essential Facts about Guns and Suicide 2016. Available from: Learn More.

- Miller M, Azrael D, Barber C. Suicide mortality in the United States: the importance of attending to method in understanding population-level disparities in the burden of suicide. Annu Rev Public Health. 2012;33:393-408. PubMed PMID: 22224886.

- Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; [cited 2016 February 2]. Available from: Learn More Here.

- Vriniotis M, Barber C, Frank E, Demicco R, the New Hampshire Firearm Safety C. A Suicide Prevention Campaign for Firearm Dealers in New Hampshire. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2015;45(2):157-63. Epub 2014 Oct 28. PubMed PMID: 25348506.

- Common Ground: Reducing Gun Access: Suicide Prevention Resource Center; 2016. Available from: Learn More Here.

- Shute N. A Plan to Prevent Gun Suicides. Sci Am. 2016.

- Nation’s Largest Suicide Prevention Organization Launches Suicide Prevention and Firearm Pilot Program 2016. Available from: Learn More Here.

- Colorado Gun Shops Work Together To Prevent Suicides: National Public Radio; 2016. Available from: Learn More Here

- Ranney ML, Fletcher J, Alter H, Barsotti C, Bebarta VS, Betz ME, Carter PM, Cerdá M, Cunningham RM, Crane P, Fahimi J, Miller MJ, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Vogel JA, Wintemute GJ, Shah MN. A Consensus-Driven Agenda for Emergency Medicine Firearm Injury Prevention Research. Ann Emerg Med. (In press).

- American Academy of Pediatrics Gun Violence Policy Recommendations2013.

Emmy Betz, MD, MPH