Celebrating Art, Healing, and Community

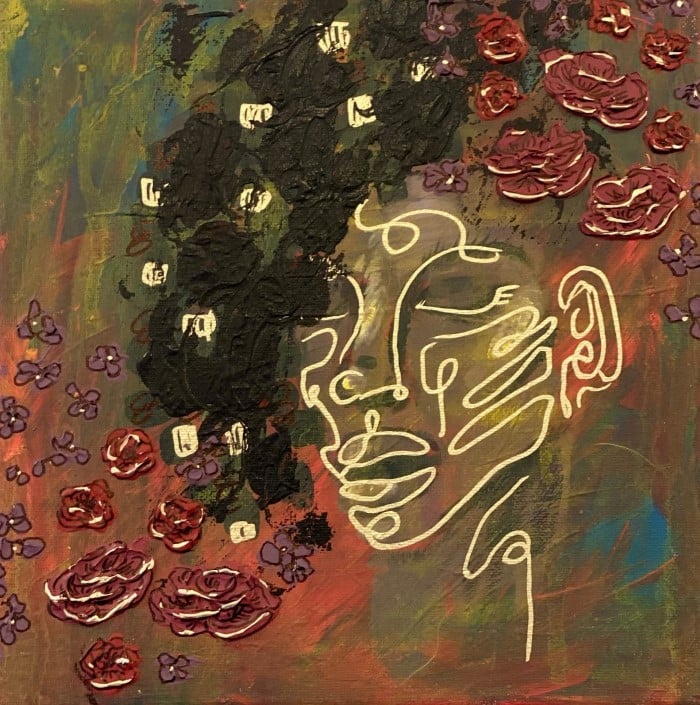

Serene

Sara Malik, DO

*Used with permission

Sara Malik, DO, accepts her award for her painting, “Serene.”

Sara Malik, DO, accepts her award for her painting, “Serene.”

Salve

Sohini Halder

*used with permission

Did you ever check out that bookstore

On the corner of Haight and something?

You would have loved it, I think.

Dusted chalk on fingers thumbing a page

The last few plastered shut forever-

I wonder how it ends.

Do you crinkle the corners like the gentle lines by your eyes?

Did you, I mean

I wonder.

“I like the lived-in look,” I remember

The flannels and esteemed fuzzy socks-

Crinkled corners it is.

The nurses try again, I hold your hand

Riddled with entry wounds and track marks and a Halloween special tattoo “Only $50!” - the deal of a lifetime

“It hurt like hell but I’ll survive.”

And so it goes

Half-laid truths and unfinished goodbyes

A stumbling halt as the bus pulls away

Grimaced laughs

Stitched in smiles

You would have hated it all

A salted balm on chapped lips

Lavender and sweat and blood

The sweet indecision of nineteen

The sickening permanence of a yielded choice.

Did you know then,

The hold you would have on me?

Room 311

A nightly station in my dreams,

My final stop after rounds

A surprising reprieve.

I wonder

All the time in the world to think on it,

No witnesses left to bear me now

That the bedsheets are changed and the room is scrubbed clean

And the smell of bleach that you despised is souring my stomach once more.

Room 311,

The indentations on my heart are all wrong

You were supposed to live.

To get better.

To be reckless and young and angry and stupid and nineteen

You were supposed to

Did you ever get the postcard I sent you?

Stamped with the Eiffel Tower on your bucket list,

Sent from the gift shop four floors below you,

Screaming “Get well soon.”

Sohini Salder accepts her award for her poem, “Salve,” from JT Finnell, MD, ACEP Board liaison.

Sohini Salder accepts her award for her poem, “Salve,” from JT Finnell, MD, ACEP Board liaison.

My Suicide Blanket

Christina Shenvi, MD, PhD, FACEP

*Used with permission.

“Did you get your suicide blanket yet, doc?”

I shook my head and he put one in my hands.

“What is it supposed to do?” I asked.

“It’s part of the hospital’s mental health improvement plan. It’s to help our wellness so we don’t all go kill ourselves,” he said dryly, “instead of adequate staffing and better pay.” Sarcasm in a thick southern drawl has a special sort of charm and sting.

I put it on my desk. The charge nurse went on to hand out more blankets to the other Emergency Department staff. I ran my hands over the material. It was coarse and pilled. The edges were straight cut with no seams. It was the kind of thing you might buy at a Dollar General in a pack of fifty.

What could this blanket do, I wondered, to save us from the despair of moral injury and institutional betrayal? Could it end the chronic micro-stresses that wear down even the kindest and strongest among us? I looked up at The Waiting room board. There were forty-five humans listed. Each of their names, their sources of pain, and the hours they had been waiting were a pinprick. Caring comes at a price. Apathy is the only way to avoid the silent reproach of the long wait times and patients stacked in chairs in hallways.

Could I throw the blanket over the monitor? Could it save us from the indignity of impotent good intentions? Could I wrap its coarse, gray fibers around me and curl up under my desk so no one would ask me any more questions? Could I roll it up and tie it around my ears and eyes so I wouldn’t have to hear any more angry complaints from exhausted family members? Could I charge out the ambulance bay doors and run around the loading dock wearing it as a cape? Could I jump off the building and use the blanket as a parachute to catch the air and float me slowly down?

Maybe I could fold the blanket into the shape of a bird and sit with it in a tree. I would tell it all the ways the day was hard. I would show it all the tiny cracks that had formed today and the ones that were still healing from yesterday. The little blanket bird wouldn’t remind me that being in healthcare is a privilege. It wouldn’t imply that the problem was me, that I should be stronger. It wouldn’t tell me to do more yoga and take care of my well-being. It wouldn’t tell me to make sure I had good sleep hygiene after I had worked overnight and then slept fitfully all morning.

I could spread it on the grass of a quiet meadow and have a picnic on it in the afternoon sun. Just me and the air and the freedom, no list of broken people waiting to be fixed or helped or appeased or medicated. I could cut it into strips, tie them together, and escape from a burning building. I could fly it like a kite, with the wind whipping around us. I could step into an arena and taunt a raging bull with it. I could tie it across my back and carry my sleeping baby in it. I could burn it for warmth on a cold day. I could catch rain in it during a thunderstorm until it was soaked and useless. I could make a fort of pillows and drape the shaggy blanket over as a roof. I could use it to line a box when I rescue a new kitten.

I could fly to the moon and stake it into the silvery dust like a flag. I would claim the moon for all the doctors and nurses who were goaded to hold onto their humanity with the gift of a cheap blanket bought with their own labor. I could lay it across my lap as an old lady in a rocking chair on my front porch, smoothing its wrinkles with slow, arthritic hands.

I could hang it on the wall like a work of art, a silent indictment of all who had the power to change things but didn’t. Its slowly fading gray strands would condemn those who reasoned that: Because the workers are still standing, they must be able to carry more. If they aren’t on their knees, then the burden must not be too heavy. Tut tut! Good teammates don’t complain. It’s weak and unladylike. Didn’t you appreciate the blanket we gave you? Good teammates say, “thank you.”

The charge nurse circled back to his desk a few feet from mine, his blankets distributed.

“What’s it supposed to do?” I asked again.

“I don’t know.” He didn’t look back, speaking to his computer screen. I watched him slowly slide his own blanket off the desk and into the trash. He didn’t take his eyes off The Waiting room screen in front of him. “I guess it’s supposed to make up for everything else.”

If you are in crisis or need help, please reach out to the physician crisis line: 800-273-8255. They will give you free support.

Christina Shenvi, MD, PhD, accepts her award for her prose piece, “My Suicide Blanket.”

Christina Shenvi, MD, PhD, accepts her award for her prose piece, “My Suicide Blanket.”