What Physicians Can Do to Help Themselves

Prepare yourself to fully participate in redesign initiatives by taking good care of yourself and cultivating a clear vision.

In the last newsletter we looked at the stress-strain process and how wellness programs that support physician resiliency can complement system redesign initiatives that identify and reduce workplace stressors. Next, we'll focus on how physicians can shape health-promoting initiatives in ways that will help them in both the short and the long term.

Because healthcare is in need of large-scale system reform, Addressing Physician Burnout: The Way Forward wisely calls for collaborative efforts between national groups, healthcare organizations, leaders and individual physicians. I believe that substantive and sustainable reform movements have already begun, and will continue to be developed over the months and years. We are living in exciting times.

But given that work system redesign is an expensive and time-consuming process, physicians often ask me: What can I do to help myself now?

I have had years to think about that question and here's my simple list:

- Step 1: Create Some Breathing Space

- Step 2: Gain Clarity for Yourself

- Step 3: Engage Others in this Conversation

This list is simple, but it’s not easy. These straight-forward actions have the potential to be transformative. If you take them seriously, they will not only improve your health in the short term, they also can shift your current work processes, leading to long-term relief.

In the first step, I'm asking you to practice self-care so that you can fully participate in necessary system reforms. (The side benefit is that it could improve your life quickly!) In Step 2, I'm suggesting that you view yourself as a change leader for a new incarnation of emergency medicine and educate yourself accordingly. Essentially, I'm asking you all to take responsibility for the evolution. We need your voice to be strong and clear.

Read on to learn more about these first two steps. I’ll devote my next and final piece to the third.

1. Create Some Breathing Space

Gather your energy so you can lead the way forward.

It’s nearly impossible to think coherently and creatively when you’re exhausted. So Step 1 is to regain your energy.

I realize this request flies against the culture of medicine and the realities of the demands you're dealing with, but I ask that you engage in more self-care. Put yourself first for a little while—maybe start with a month and see how it goes?

Here’s the thing: when you are feeling more yourself, you will be able to see possibilities for change that will not only help yourself, but also will help your colleagues, your patients and your family.

Edy Greenblatt did some interesting research on how professionals become exhausted. Her book Restore Yourself: The Antidote for Professional Exhaustion provides a structure to think about how you gain energy or lose energy throughout your week—at work and at home.

It’s an easy read, and it could be a way to connect with your partner, a friend or a good colleague. Read or skim it together and talk about where you find restoration and what things drain you. Then take an action—just one action—to increase what restores you or decrease what drains you.

Here are some other ideas for your breathing space:

- Participate in one of your organization’s wellness initiatives

- Make your favorite restorative practice a priority again (e.g., meditation, yoga, exercise, mindfulness, sleep)

- Take rest breaks when you need them, even if it unsettles the people around you

- Schedule a personal retreat—and don’t work through it!

This breathing space is essential. We need your energy and insight as a leader, which leads into Step 2.

2. Gain Clarity for Yourself

Determine what a successful practice looks like through the lens of a health-promoting system.

I ask that you consider yourself a change leader, no matter what your title. As a physician, you know what effective emergency medicine should look and feel like. You have been working toward it even in the midst of distractions, obstacles and exhaustion.

For any reform initiative to be successful and sustainable, we (your system collaborators) need to understand your vision. Only when we share a common understanding of medicine’s goals, values and priorities can we work together to shape what comes next.

I believe that a large part of the reason our current healthcare system has moved so far away from health is because the people doing the work did not participate fully (for a variety of reasons) in the design of the work system. The current systems are designed through other lenses (e.g., profitability, standardization, efficiency, etc.). Those lenses are fine when they are subordinate to the greater goals of caring, health and healing. But when those additions replace the ultimate goals, they deform the system.

So my first request is that you practice communicating your vision of effective emergency medicine. Second, in order for that new vision of effective emergency medicine to be sustainable, we need you to integrate it with a healthy way of working.

In order to spark some ideas about what that could look like, let's begin to explore health-promoting work.

Designing work for human beings

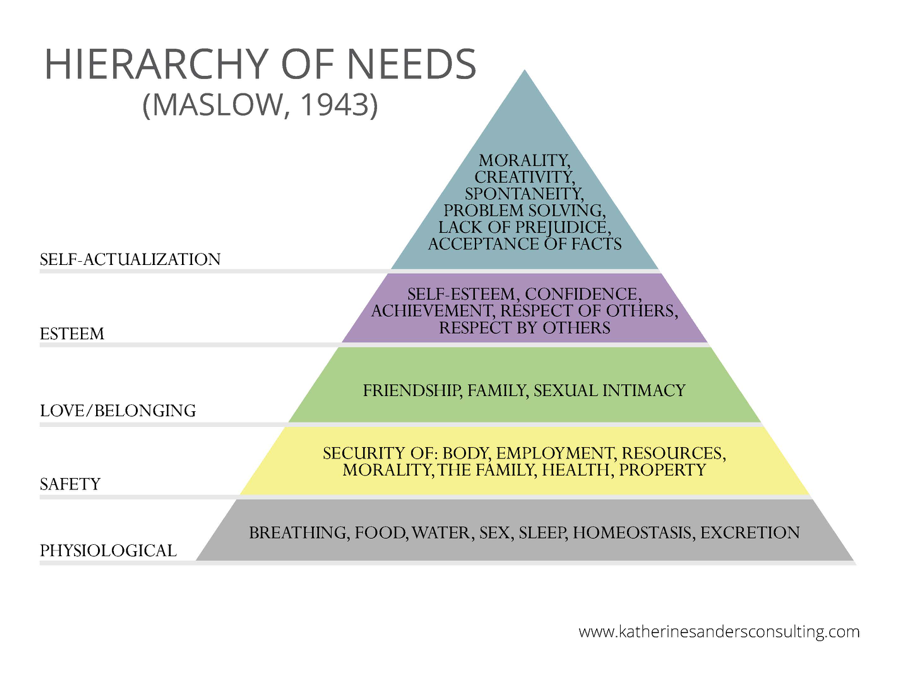

Remember Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (Figure 1) from your intro psychology class?

Fig 1.

Health-promoting work helps us meet our needs.

It’s an investment, but it is possible to design work systems in which people have many of their needs met. Work can help us pay our mortgage and meet our needs for survival and safety, but it also can contribute to our sense of love and belonging, our self-esteem and our growth. Money is necessary and useful, but many times it is conflated with value and respect.

We must design work so people can make their best contributions and be recognized for them. This might be related to working “at the top of your license.” It’s definitely related to our experience of autonomy, challenge and social support. People seek self-esteem and the respect of others at work. It’s expected and healthy. We must design work to support these experiences.

Equally important, we must design work to minimize stressors that prevent people from meeting their needs. Workplace stressors that prevent us from experiencing safety, love, belonging, self- and peer-esteem and growth have to be addressed.

For example, if the workload is set unrealistically high, work can be so time-consuming that it interferes with loving relationships and a sense of belonging with family, friends and colleagues.

Also, we need to take special care to design safe spaces for those working in high-risk environments. Physical and psychological safety is essential to health. The art will be to design physical and social spaces where people can retreat to restore themselves and feel understood. And in order for those designs to be effective, people will need to have the time to take part in them.

Reducing dissatisfaction and preserving motivators

Because no workplace is perfect and all organizations have finite resources, it is vital to prioritize our needs. We need to know where to start, what to preserve, and what to change.

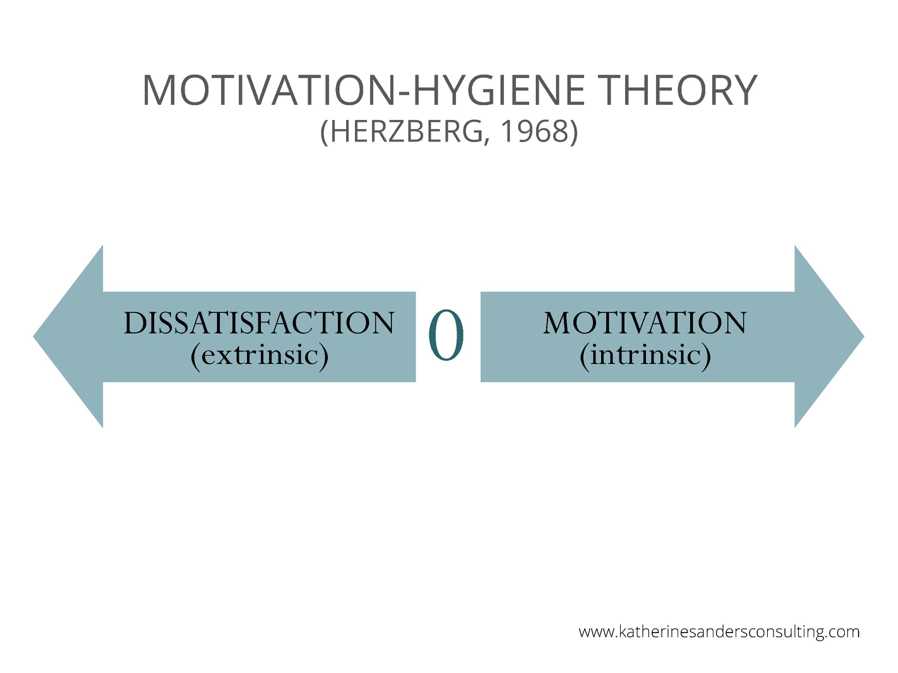

Psychologist Frederick Herzberg (Figure 2) made a huge contribution back in the 1960s that can help us prioritize where to begin. He studied job satisfaction and found employee engagement and employee dissatisfaction were actually two separate phenomena. In other words, what causes us to be engaged and intrinsically motivated has little to do with what causes us dissatisfaction.

Fig 2.

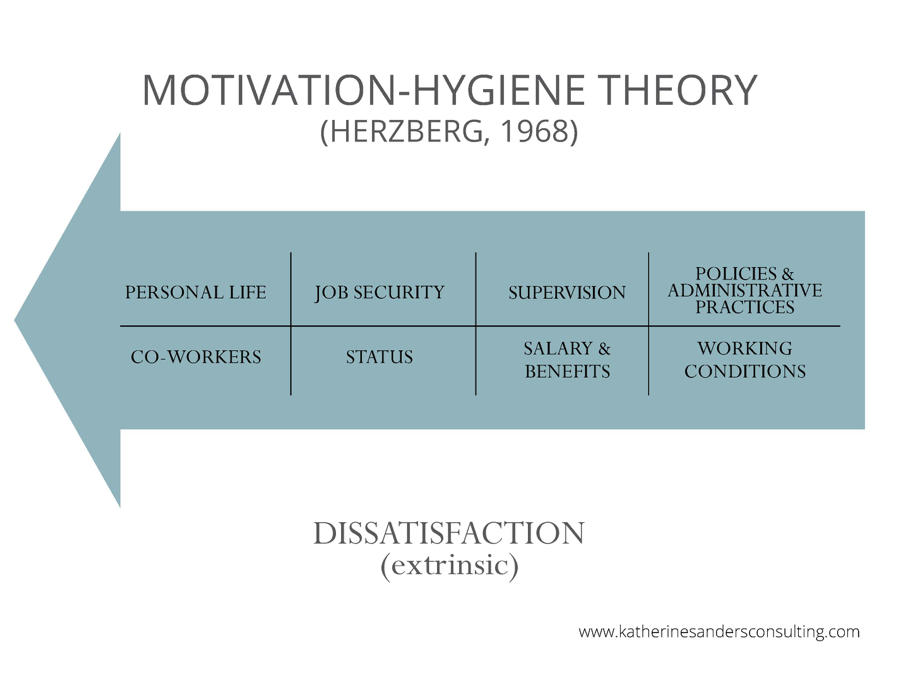

As it happens, there are some parts of work that, even at their very best, can only take us to a lack of dissatisfaction (Figure 3). If those needs are met we feel neutral. We experience no dissatisfaction.

Fig 3.

Things like our salary, our relationship with our supervisor, our working conditions and the policies of our organization are important to us, but when these needs are met fully, we are merely not dissatisfied. They don’t increase our commitment to do our best work because they aren't related to intrinsic motivation.

Herzberg called these factors “hygiene factors,” and they make up much of the foundation of Maslow’s Hierarchy. They need to be addressed but, by themselves, they are not enough.

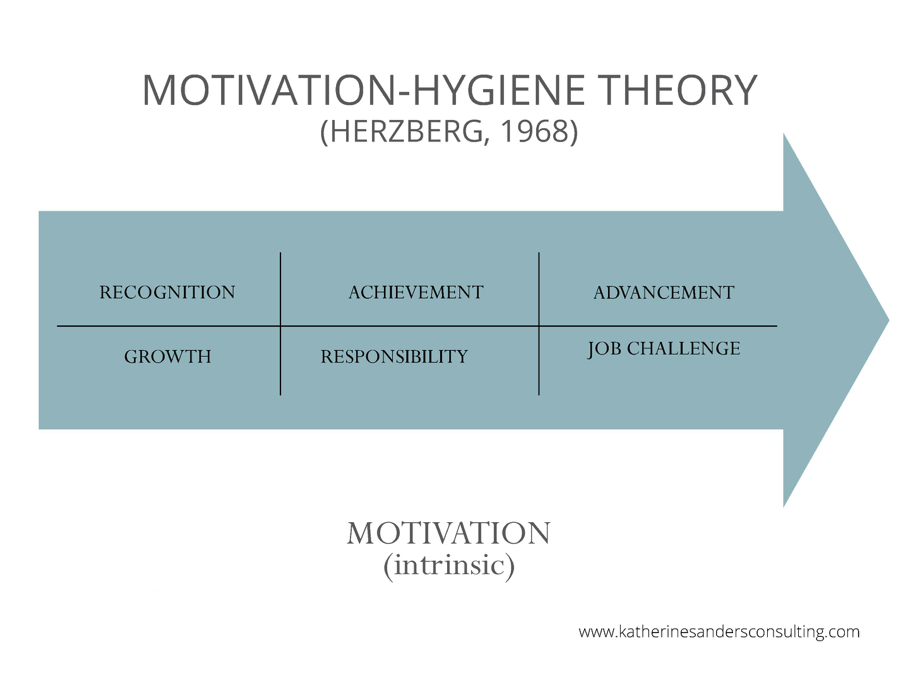

In contrast, Herzberg put forward “motivators” on a completely different scale (Figure 4).

Fig 4.

He found that factors such as a sense of challenge, achievement, recognition, growth, responsibility and advancement were associated with intrinsic motivation. Located on the highest levels of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, this is where engagement and joy in practice live. This is where work shines. This is where your calling as a physician lives.

The researchers that follow Herzberg continue to clarify lists of motivators. (See the resources section, below.) They include intrinsic drives that people have for purpose, autonomy, skill variety, challenge, appreciation and making progress toward meaningful goals.

The brilliance and practicality of Herzberg's contribution is that it clarifies that dissatisfaction doesn’t have to do with engagement. You can be very dissatisfied with your pay and dislike your organization’s policies but still love your work.

I believe many physicians feel this way. They love their patients and still feel called to medicine. But they are dissatisfied with the ways certain work system factors have been designed.

When dissatisfiers are not addressed and motivators are designed out of our work, the results are low levels of engagement, high levels of dissatisfaction, and eventually poor mental and physical health outcomes. In these environments we can expect to see increased errors, and higher rates of absenteeism, presenteeism (coming to work sick) and turnover.

When we reach this place of ill health, some organizations offer salary increases (a hygiene factor) in an attempt to increase engagement. What they don’t realize is that that the problem is actually a lack of intrinsic motivators: autonomy, meaning, challenge and/or appreciation. If conflated with appreciation, a boost in pay may be a temporary Band-Aid for feeling invisible. But the best a higher salary will do is eliminate dissatisfaction with pay.

Preparing to Lead Change

This is why your clarity is essential when redesign initiatives take place.

Physicians must be able to communicate which parts of their practice feed their intrinsic motivation and therefore should be preserved or regained. Equally important, they need to know how to identify and prioritize dissatisfiers for themselves and their teams. This isn't something that can be done by outsiders, no matter how well intended.

I’ll add one side note for your team members’ sake. We have to be careful not to off-load physician dissatisfiers to other professions, if those tasks also erode meaning for them. Health-promoting work systems require the entire team be engaged in meaningful work and experience a sense of achievement. We'll have to think creatively about data entry and documentation so that it doesn't overwhelm anyone's job description.

Next time I’ll talk about Step 3, Engage Others in this Conversation. After you have restored your energy and gained some clarity, it's time to seed change by beginning to talk with your colleagues in a constructive way. With intention and persistence, it is possible to shift your organization toward more health.

Resources

Books you might want to read with colleagues and/or loved ones:

- Edy Greenblatt, Restore Yourself: The Antidote for Professional Exhaustion

- Christina Maslach, Burnout: The Cost of Caring

- A literature review that summarizes important workplace stressors:

- E. Kevin Kelloway and Arla L. Day, Building Healthy Workplaces: What We Know So Far

- For more information about the intrinsic motivators that lead to engagement and health:

- J. R. Hackman, “Job Characteristics that Foster Internal Work Motivation” in Leading Teams: Setting the Stage for Great Performances.

- Teresa Amabile and Steven Kramer, The Progress Principle: Using Small Wins to Ignite Joy, Engagement, and Creativity at Work

See my sites for additional resources and in-depth descriptions of a systems approach to work redesign and the benefits of healthy work.