Disinfection

Jess Koehler, MD and Nik Theyyunni, MD, FACEP, University of Michigan, Department of Emergency Medicine

Love it or hate it, cleaning is a part of life - because we love it (and because it’s evidence-based) let’s talk about ultrasound machine cleaning. As we all aim to decrease the amount of time we have machines down, the knowledge of how to keep machines and probes clean and disinfected in a way that follows society guidelines is crucial. There has been a lot of back and forth about this topic over the last few years; this article aims to present a summary of the current recommendations from ACEP and the American Institute of Ultrasound Medicine (AIUM).

You encounter a dirty machine and a blood covered probe in the hallway in your ED. How do we describe all the cleaning that needs to happen? The first thing to understand is the distinction between cleaning and disinfection. Cleaning is defined as the removal of visible soiling from the surface of the probe, to prepare it for the next step of disinfection.1 Per AIUM’s 2022 guidelines, cleaning involves removing obvious gel or other debris from the probe.2 This is when a towel or wipe would be used to remove excess gel mounds on the probe before moving on to disinfection.

Disinfection is the thermal or chemical destruction of pathogens.1 Most of this article will focus on disinfection. Disinfection is divided into levels; the levels are determined by the pathogens that will be destroyed.3 Tuberculosis (TB) is not a blood-borne pathogen but is used as a marker of potency and efficacy of the disinfectant. Below are the levels of disinfection:

- High Level (HLD): removes bacterial spores

- Intermediate Level (ILD): removes bacteria, including TB

- Low Level (LLD): removes most bacteria, excluding TB3

High level disinfection often involves the submersion of the probe into the disinfectant.2 This disinfectant could be glutaraldehyde, hydrogen peroxide, or any other in the FDA list.2 Importantly, this process takes the probe out of circulation for a period of time while it is disinfected. There is a newly FDA-approved wipe that is a HLD, Tristel ULT, that has been in Europe for a few years and is therefore already listed as compatible with many transducers.4

The next point to understand is that each transducer is broken down into one of three categories by the intended type of use based on the Spaulding criteria, which is used for all medical devices.2 The key word to remember is “intended” use, this will be discussed in more depth as we go. The first category to know is noncritical, these are devices intended to be used on intact skin, like using a phased array probe to do an echo on a patient’s chest wall.1 Semi-critical is the next category and it includes probes whose intended use is to come in contact with mucous membranes, this would include TEE or endocavitary probes.1 Critical devices are not typically used in emergency medicine as they are placed in sterile body cavities, for example, intracardiac or intravascular probes.1

While talking about probe covers it is important to know which procedures need to have a probe cover. Again, AIUM’s guidelines spell this out. This guideline recommends a single use cover for any contaminated intact skin, non-intact skin, needle placement, or mucus membrane imaging.2 Leaving clean and intact skin as the only time to not use a cover. Importantly, if the sterility of the procedure determines the sterility of the probe cover.2 Peripheral lines are not sterile procedures so a single use non-sterile cover is sufficient, but an arterial line is sterile procedure and thus requires a sterile probe cover. This then brings up the question of what is a single use probe cover? Probe covers are defined by the pore size, or the maximum sized pathogen that could get through, <30nm blocks most viruses.1 If an IV dressing has a small enough pore size, though, they should not be used as they are labeled for their intended use as a dressing, not a probe cover.3 As a note, adhesive probe covers are available.

The confusion of recent years stems from the key point of the Spaulding criteria, the intended use of each object. The example often used is a probe intended for use to perform a percutaneous procedure on intact skin, such as placing a central line or peripheral line. During these procedures, the provider will place a probe cover over the probe. So, what if the probe cover fails and the probe comes into contact with blood? A 2021 intersocietal position statement addressed this and advocated that the intended use of the equipment is what matters, therefore if a probe cover fails then the probe should be treated as contaminated, but cleaned by a low level disinfectant that is effective against blood-borne pathogens.2,5 This concept applies to all situations that typically require a probe cover and LLD, so if the probe cover fails on non-intact or contaminated skin, the transducer would still require LLD based on its intended use.

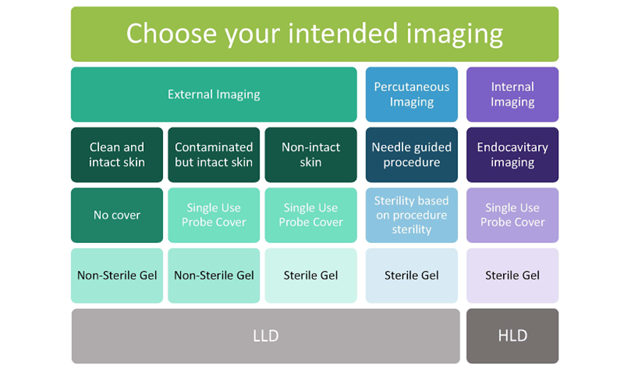

As for the gel that should be used, AIUM recommends sterile gel for procedures, mucous membranes, and non-intact skin.2 ACEP goes a step further and recommends sterile gel for ultrasound done near a recent surgical site.1 For a quick guide, see figure 1 below that is adapted from this article.

To summarize, knowing what type of imaging you are planning to do will guide your decisions on probe cover, gel sterility, and level of disinfection.

Figure 1. Summary of best practices for probe covering and disinfection. Adapted from AIUM 2022 Guidelines Procedural Graphic.2

Figure 1. Summary of best practices for probe covering and disinfection. Adapted from AIUM 2022 Guidelines Procedural Graphic.2

References

- Guideline for Ultrasound Transducer Cleaning and Disinfection. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;72(4):e45-e47. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.07.035

- AIUM Official Statement: Guidelines for Cleaning and Preparing External- and Internal-Use Ultrasound Transducers and Equipment Between Patients as Well as Safe Handling and Use of Ultrasound Coupling Gel. J Ultrasound Med Off J Am Inst Ultrasound Med. 2023;42(7):E13-E22.

- Nomura JT, Kumetz C. Update on Ultrasound Disinfection. ACEP Emergency Ultrasound Section. Published January 31, 2022. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.acep.org/emultrasound/newsroom/january-2022/update-on-ultrasound-disinfection

- Martonicz TW. Parker’s High-Level Disinfectant Foam Receives FDA de novo Clearance. Infection Control Today. Published July 19, 2023. Accessed March 15, 2024. https://www.infectioncontroltoday.com/view/parker-s-high-level-disinfectant-foam-receives-fda-de-novo-clearance

- Disinfection of Ultrasound Transducers Used for Percutaneous Procedures: Intersocietal Position Statement. J Ultrasound Med. 2021;40(5):895-7.