Cardiac Tamponade

Zachary Boivin MD, Section of Emergency Ultrasound, Department of Emergency Medicine, Yale School of Medicine

Robert T. Stenberg, MD, FACEP, Cleveland Clinic Akron General

Case Presentation

A 72-year-old female presented to the emergency department with difficulty breathing. She reports that she has been having increasing shortness of breath while walking, and now can only walk a few steps without having to stop and catch her breath. She denies other symptoms including fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, leg swelling, or syncopal episodes. She was tachycardic to 105 bpm, and her blood pressure was 104/74 mmHg. A cardiac point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) was performed to assess for causes of shortness of breath.

In the parasternal long axis view (Video 1), there appears to be a circumferential pericardial effusion, which was confirmed in the subxiphoid view (Video 2).

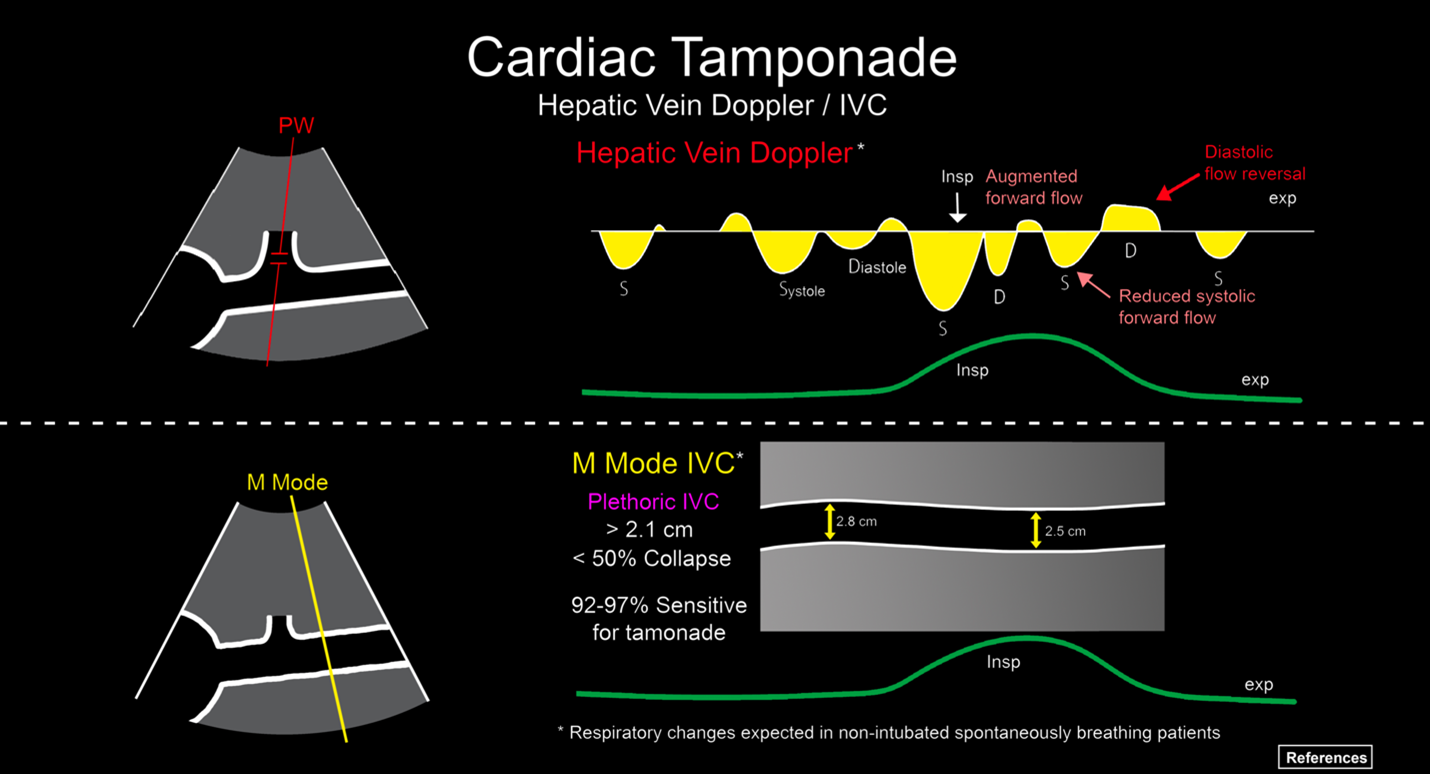

The ED physician evaluated the patient’s inferior vena cava (IVC) (Video 3), which appeared plethoric with minimal respiratory variation.

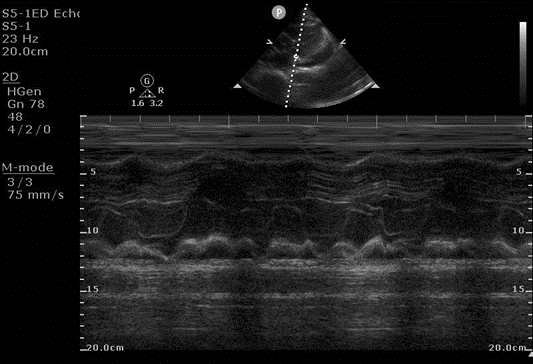

The ED physician then performed two measurements. First, they obtained a parasternal long axis view and placed an M-mode line through the right ventricular free wall and the mitral valve (Figure 1), showing diastolic collapse of the right ventricle.

Figure 1. M-mode image of right ventricular diastolic collapse, occurring when the mitral valve is open.

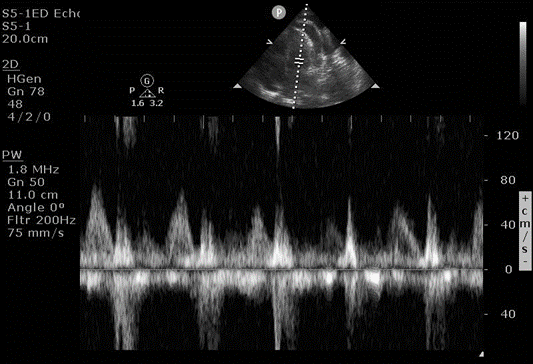

An apical four chamber view was obtained, and a pulsed wave Doppler was placed in the left ventricle, and an E and A wave were generated over the patient’s respiratory cycle. (Figure 2) This showed a > 30% variation in the E wave, suggesting sonographic pulsus paradoxus.

Figure 2. Mitral valve inflow velocity with pulse wave Doppler, showing variation in the E wave (first peak) over a respiratory cycle

Background

POCUS can help the ED physician distinguish between pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade. An effusion can be characterized on size during end diastole, with a small effusion measuring less than 1cm, a moderate effusion between 1-2cm, and a large effusion greater than 2cm. The size, however, does not determine the presence of cardiac tamponade, however, and the ED physician must use additional tools to make the diagnosis such as history and vital signs. Often, a larger effusion suggests a more chronic etiology such as a malignant effusion or uremia, as opposed to an acute traumatic cause, as the pericardial sac distends if the fluid accumulates slowly over time.

In the parasternal long axis view, a pericardial effusion can be differentiated from a pleural effusion as a pericardial effusion will track anterior to the descending thoracic aorta, compared to posteriorly for a pleural effusion. An effusion is also typically anechoic, and must be differentiated from a normal pericardial fat pad which has a speckled appearance, is primarily seen anteriorly (versus posterior for a small pericardial effusion and circumferential for a large effusion), and moves with the heart. Often, decreasing depth or zooming in on the area can highlight these differences.

The use of M-mode in Figure 1 is an easy way to distinguish whether the right ventricle wall collapses during diastole, as the opening of the mitral valve is easily visualized on M-mode as the start of diastole. Other ways to determine diastole would be to slow playback speed on the machine when reviewing the clips, or to use cardiac leads to determine systole (QRS) versus diastole (T wave).

The right atrium collapse during systole is likely to happen prior to right ventricle collapses during diastole. These inversions may not occur in the setting of elevated right heart pressure, as tamponade occurs when the pericardial pressure is higher than the right heart pressure. Right atrial diastolic collapse is best visualized in the apical four chamber or subxiphoid views, but can be difficult to visually assess, so other findings should be used to help assess for tamponade.

The use of the IVC helps assess for risk of cardiac tamponade, as a plethoric IVC is the most sensitive sign of cardiac tamponade. While a patient can have a normal or flat IVC in the setting of tamponade, it requires a low blood volume due to hemorrhage or massive gastrointestinal losses and is exceedingly rare.

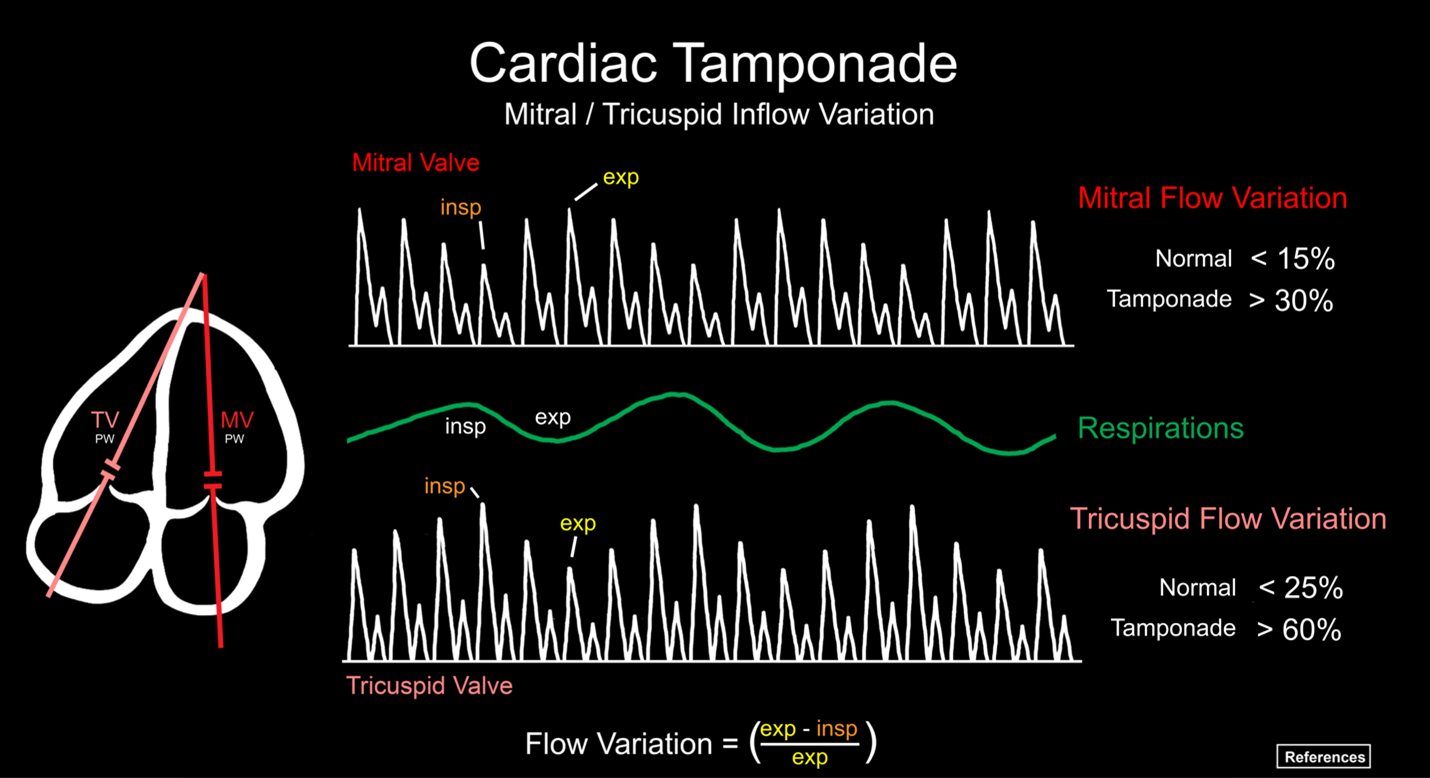

Looking at respiratory variation in blood flow through the mitral valve is often thought of as difficult to acquire but can be performed reliably after practice. A good apical four chamber view is a necessity, and the pulsed wave Doppler gate is placed within the left ventricle at the coaptation of the mitral valve leaflets, generating an E wave first (early diastole) and an A wave second (atrial kick). The ED physician should ask the patient to take a breath, and an E and A wave are generated throughout the respiratory cycle. The image is frozen, and the amplitude of the largest and smallest E wave is measured. Figure 2 If the difference is greater than 30%, this finding is very specific for cardiac tamponade. While this same approach can be performed using the tricuspid valve, the right ventricle can be more difficult to obtain a clear view of, and the difference in E wave amplitude must be greater than 60% to be considered positive. While other sources say the mitral valve needs greater that 25% variation, and the tricuspid valve needs greater than 40% variation for tamponade, using 30% and 60% respectively will increase specificity.

Cardiac tamponade can be difficult to diagnose sonographically, and a recent paper by Schaeffer et al. polled members of the AEUS and found poor interrater reliability across 20 cardiac POCUS video clips. Specifically, the study shows disagreement regarding abnormal septal motion, and both right atrial and right ventricular collapse. This highlights the difficulty making the diagnosis based on POCUS alone, and the patient’s symptoms and vitals should be taken into account when diagnosing cardiac tamponade.

Case Resolution

The patient was found to be in cardiac tamponade, with approximately 300cc of fluid drained off in the catheterization laboratory. Further workup showed a malignancy, which the patient began receiving treatment for. The emergency department POCUS was instrumental in making an immediate diagnosis, and getting the patient prompt management.

Series

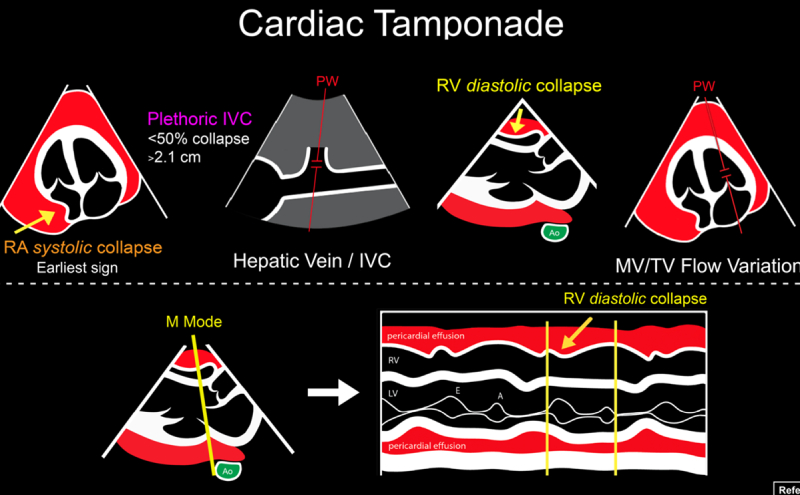

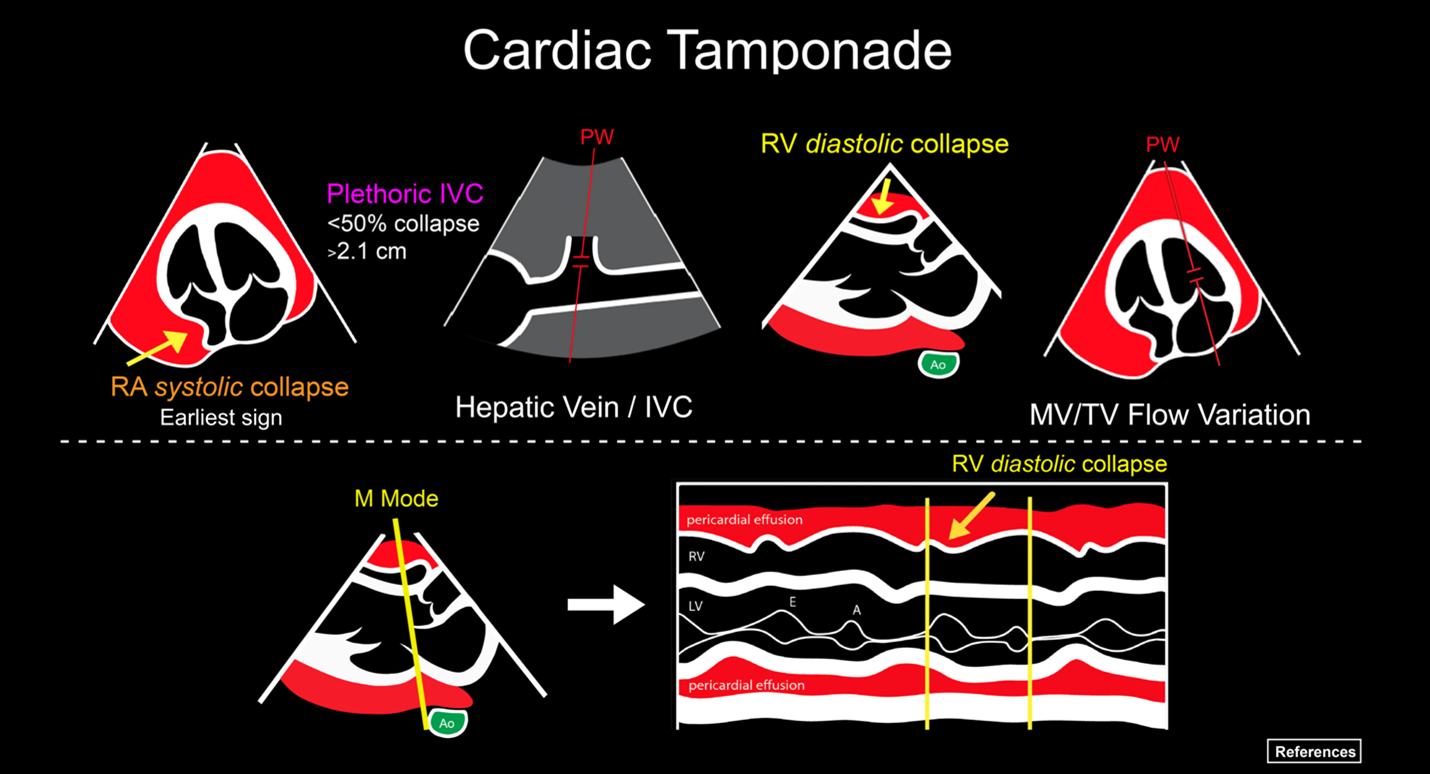

ACEP’s Critical Care Ultrasound Subcommittee has been working on advanced cardiac ultrasound educational cards to share with the community as a reference when performing critical care bedside ultrasound. The cardiac tamponade card is attached, and it is a useful tool to have when you need a quick reminder. Stay tuned for more to come from the group!

This was my middle ground to address it, some of the articles in ACEP US Newsletter use citations, so perhaps I can just do some basic citations if people want more info?

Resources

Schaeffer WJ, Elegante M, Fung CM, Huang R, Theyyunni N, Tucker R. Variability in Interpretation of Echocardiographic Signs of Tamponade: A Survey of Emergency Physician sonographers. J Emerg Med. 2024;66(3):e346-e353.

Bella S, Salo D, Delong C, et al. Agreement on Interpretation of Point-of-Care Ultrasonography for Cardiac Tamponade Among Emergency Physicians. Cureus. 2023;15(7):e41913.

Walsh BM, Tobias LA. Low-Pressure Pericardial Tamponade: Case Report and Review of the Literature. J Emerg Med. 2017;52(4):516-22.

Hoit BD. Pericardial Effusion and Cardiac Tamponade in the New Millennium. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2017;19(7):57.

Alerhand S, Adrian RJ, Long B, Avila J. Pericardial tamponade: A comprehensive emergency medicine and echocardiography review. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;58:159-74.

Hoch VC, Abdel-Hamid M, Liu J, Hall AE, Theyyunni N, Fung CM. ED point-of-care ultrasonography is associated with earlier drainage of pericardial effusion: A retrospective cohort study. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;60:156-63.