Gender and Diversity Within Disaster Management: A Framework for Effective Analysis

Rachel Thomas, MA

Recent improvements in disaster management are mainly due to technological advancements, state-of-the-art preventive computer mapping, and decreased aid arrival times. However, adult males of the dominant socioeconomic and religious classes continue to be prioritized in disaster situations. This has been shown to be true for both man-made (e.g., chemical, biological weapons) and natural (e.g., earthquakes, pandemics) disasters.

A large body of evidence supports that natural disasters and pandemics affect men and women differently due to gender-based cultural and societal roles and responsibilities. For example, during the 2004 earthquake and subsequent tsunami in the Indian Ocean which killed approximately 230,000 people, 70% of the casualties were female. Retrospective analysis of the event highlighted cultural prohibitions on teaching females to swim and climb trees made them less able to survive in floodwaters; the timing of the event meant that most females were at home while males were at their places of employment; women’s garments made running and swimming more difficult; and women were more likely to stay behind to attempt to rescue family members. Understanding these disparities is not only important, but also essential to saving lives and gaining rapid control of disaster events. Performing intentional internal and external gender analysis can facilitate more comprehensive, inclusive, and effective solutions - streamlining the equitability of response and setting the stage for recovery.

Gender Analysis Framework (Adapted from Turner, Thomas, Keys: Gender Analysis Framework)

External Questions: Questions about how we conduct crisis response.

- Are systems in place to collect/track/publish relevant sex-disaggregated data?

- Is data being disaggregated by sex? Is there a difference in terms of infection and mortality rates? If so, what are the biological and social factors causing this?

- Who cares for the ill, both in formal settings (hospital) and informal settings (at home)?

- Are those caring for the ill being fairly compensated/supported?

- Who is making disaster response decisions? Is the organization aware of the differing social/cultural necessities of the community? How are they ensuring that all subpopulations and groups are being accounted for in plans?

- How will different groups of people, particularly marginalized communities, be affected by any stigma associated with the disaster? How can this stigma be countered (e.g. racism against persons of Asian descent)?

- Are there specific groups that might avoid surveillance/testing/care because they distrust the government and/or healthcare services? How can they be reached/ protected?

- Are both women’s and men’s healthcare needs being met (e.g., maternal care, psychosocial support, contraceptives)?

- Do pregnant women have access to care, pre- and postpartum?

- Are sexual and reproductive supplies (such as contraception) readily available?

- Will equipment/medications/other commodities diversions decrease access for at-risk populations?

- Will disruptive measures affecting normal patterns of activity and movement within a society increase the risk for certain genders?

- Who controls information communication technologies/systems? Who has access to those systems? Are we selecting media that are accessible to men/women/children?

- Have we accounted for information sharing systems that are no longer reliable? What have we done to adjust communications to ensure we can reach men/women/children?

Internal Questions: Questions about how we build our crisis-response teams.

- What are the family situations of our response team? Do they have adequate access to safe childcare? Are they prevented from attending work due to childcare concerns?

- Will their involvement with response put others at risk (e.g. elderly family members)?

- Will their involvement in this response put an undue financial burden on them? Do we have ways of tracking intimate partner violence? Do all team members know where to go, and how/where to refer at-risk individuals?

- Are we selecting our team members to representative of the population (male, female, ethnicity, religious affiliation in some cases, etc.)?

Do all teammates have training on gender-responsive approaches, gender-based violence (risk, recognition, and reporting), how to recognize/report human trafficking, and how to perform basic gender analysis?

Policy Check: Questions to improve policy. Practitioners should further ask these questions, considering the possible shifts within each category.

- Are women’s and men’s needs/priorities different in the context of the proposed policy?

- What roles do women and men perform in the context of the policy?

- What resources/information (e.g., financial, physical) do women and men have access to?

- Are there existing roles/responsibilities/opportunities for men and women that the proposed policy will be affected?

- Do women and men have equal access to/influence over policy development and decision-making? If not, how can we ensure that we include non-represented groups?

- Are services/technologies provided by policy available/accessible to women and men?

- Do follow-up protocols address the needs of specific groups (e.g., families with children, persons with disabilities, socioeconomic groups, LGBTQI communities)?

After every question, the practitioners should ask: Can we influence this? Do we know who can? Should we make a recommendation to policy/decision makers regarding this gendered effect?

Feedback Loop and Reporting Procedures:

Ensure a feedback loop is present. If, after review of implemented policies, they are not productive or are producing unintended negative effects, these strategies must be modified.

- As well as possible, establish a baseline of current operations.

- Closely track data gathered and review trends.

- Create a collaborative review group* to discuss trends.

- Identify any problem areas and modify as necessary.

- Continue this feedback loop throughout the process.

*Collaborative groups should include those on the frontline, along with planners.

References:

A GENDER-SPECIFIC EARTHQUAKE RECOVERY ASSESSMENT USING ADMINISTRATIVE AND SATELLITE DATA. Sonia Akter, Talitha Fauzia Chairunissa, Madhavi Pundit, and Marcel Schroder. file:///C:/Users/G25504285/Downloads/SSRN-id4317344.pdf.

Turner, Thomas, Keese. “Gender Analysis Framework: COVID19 V4.” Google Doc, Google, 22 April 2020.

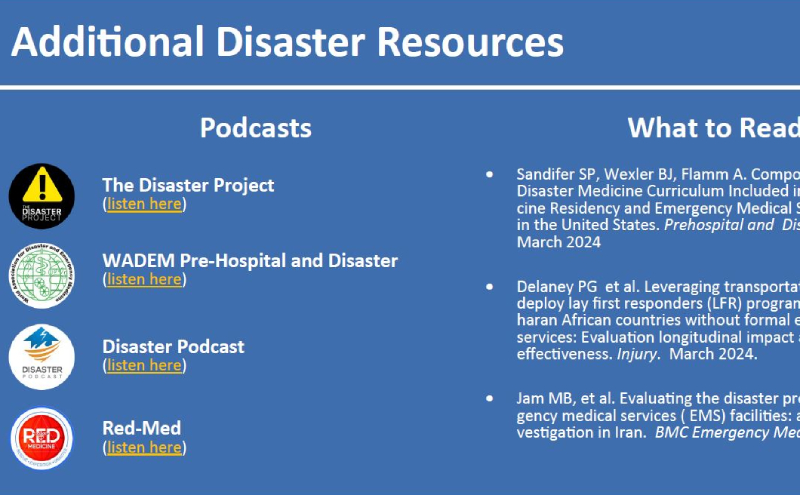

Additional Disaster Resources

Podcasts:

The Disaster Project

WADEM Pre-Hospital and Disaster

Disaster Podcast

Red-Med

What to Read:

- Sandifer SP, Wexler BJ, Flamm A. Components of an Updated Disaster Medicine Curriculum Included in Emergency Medicine Residency and Emergency Medical Services Fellowship in the United States. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine. March 2024

- Delaney PG et al. Leveraging transportation providers to deploy lay first responders (LFR) programs in three sub-Saharan African countries without formal emergency medical services: Evaluation of longitudinal impact and cost-effectiveness. Injury. March 2024.

- Jam MB, et al. Evaluating the disaster preparedness of emergency medical services (EMS) facilities: a cross-sectional investigation in Iran. BMC Emergency Medicine. March 2024